A “restrictive modifier” is a word, phrase, or clause that provides essential information needed to identify which specific person, place, or thing you’re discussing. This modifier “restricts” or narrows down the meaning of the noun it describes, making it crucial to the sentence’s core message. Without a restrictive modifier, the sentence becomes unclear or changes meaning entirely because you lose the identifying information. For instance, in “Students who study regularly earn better grades,” the clause “who study regularly” is restrictive—it specifies which students earn better grades, not all students in general. Remove this modifier and you get “Students earn better grades,” which incorrectly suggests all students earn better grades regardless of study habits.

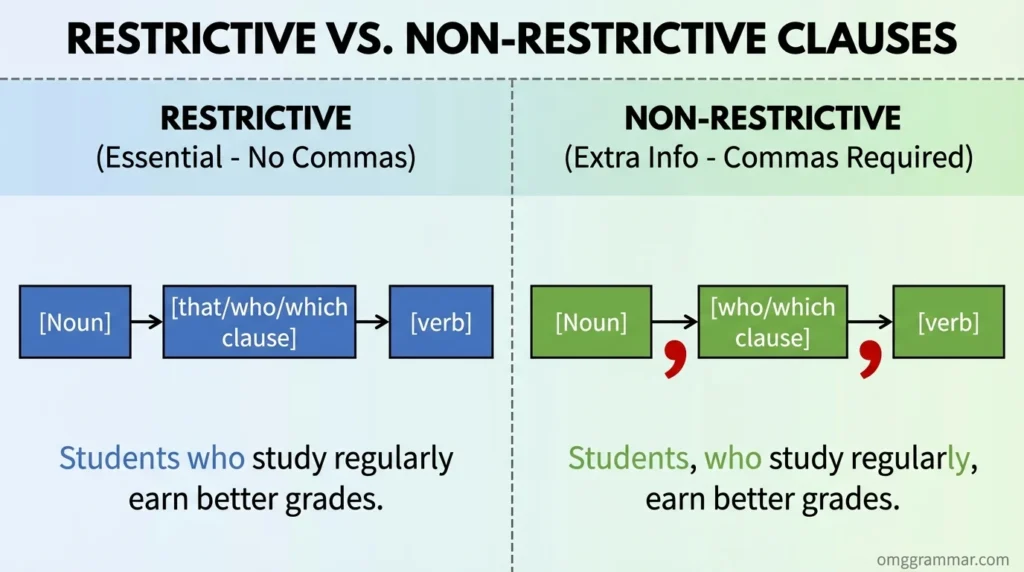

The key grammatical marker: restrictive modifiers never take commas because they’re integral to meaning. They differ from non-restrictive modifiers, which add extra information but aren’t essential to identifying the noun.

Understanding this distinction prevents punctuation errors and ensures your sentences communicate precisely what you intend, particularly in professional, academic, and legal writing where ambiguity creates problems.

What Is a Restrictive Modifier?

A restrictive modifier is any grammatical element—adjective, phrase, or clause—that narrows the meaning of a noun by providing necessary identifying information. The term “restrictive” means the modifier restricts or limits the noun to a specific subset.

Think of restrictive modifiers as filters. Without them, your noun refers to an entire category. With them, you’re pinpointing exactly which member of that category you mean. The sentence “The book is on the shelf” could refer to any book, but “The book that I borrowed from you is on the shelf” uses a restrictive clause to specify exactly which book.

Restrictive modifiers appear in several forms. Restrictive clauses (dependent clauses starting with “that,” “who,” “which,” or “whom”) are most common: “The employee who arrives first opens the office.” Phrases also work: “The woman in the red coat is my boss” uses a prepositional phrase restrictively.

The critical test: Can you remove the modifier without changing which specific thing you’re talking about? If removing it makes the sentence unclear or changes the meaning, it’s restrictive. If the sentence still identifies the right noun without it, the modifier is non-restrictive.

How Do Restrictive Modifiers Work in Sentences?

Restrictive modifiers function by adding essential information directly to the noun they modify. This information isn’t optional commentary—it’s the identifying detail that tells readers which specific noun you mean.

Consider sentence structure. In “Dogs that bark constantly annoy neighbors,” the clause “that bark constantly” sits right after “dogs” and restricts the subject to a specific type of dog. The sentence isn’t about all dogs; it’s specifically about constantly barking dogs. The modifier creates a subset within the larger category.

The grammar mechanics are straightforward. Restrictive clauses typically begin with relative pronouns: “that” for things, “who” for people, “which” for things (though “that” is preferred in American English for restrictive clauses about things). The clause follows the noun immediately and integrates into the sentence structure without interruption.

Position matters. Restrictive modifiers must stay close to the noun they modify to maintain clarity. “The report that contains the financial data is confidential” keeps the clause next to “report.” Moving it creates confusion: “The report is confidential that contains the financial data” sounds awkward and unclear.

When editing legal contracts, I notice restrictive clauses carry enormous weight. “The party that breaches this agreement must pay damages” differs critically from “The party must pay damages.” The restrictive clause defines which circumstances trigger the penalty—removing it changes the contract’s entire meaning.

How Do You Punctuate Restrictive Modifiers?

The golden rule is simple: never use commas with restrictive modifiers. Commas signal non-essential information, but restrictive modifiers provide essential information. Adding commas changes the meaning.

The Golden Rule: Restrictive modifiers integrate into sentences without commas because they’re essential to identifying the noun. Setting them off with commas incorrectly signals optional information.

Compare these sentences:

- “The students who studied hard passed the exam.” (Restrictive—only students who studied hard passed)

- “The students, who studied hard, passed the exam.” (Non-restrictive—all students passed, and incidentally they studied hard)

The comma difference changes whether you’re describing a subset of students or all students. This matters significantly in professional writing.

In academic manuscripts, I frequently correct comma errors with restrictive clauses. Authors often write: “The research, that supports this hypothesis, was conducted in 2024.” Those commas are wrong. The clause “that supports this hypothesis” is restrictive—it specifies which research. Correct punctuation: “The research that supports this hypothesis was conducted in 2024.”

American English strongly prefers “that” for restrictive clauses about things, which helps prevent comma errors. “The car that needs repair” signals a restrictive clause automatically. British English uses “which” for both restrictive and non-restrictive clauses, making punctuation even more critical there.

Examples of Restrictive Modifiers in Action

Correct Usage in Different Contexts

Professional writing relies heavily on restrictive modifiers for precision. Business documents use them constantly: “Employees who complete the training receive certification.” This specifies which employees get certified—not everyone, just those completing training.

Legal writing demands absolute clarity through restrictive modification. “The provisions that govern termination appear in Section 12” directs readers to specific provisions, not all provisions in the document. Across hundreds of legal document edits, I’ve seen ambiguity lawsuits arise from missing or incorrectly punctuated restrictive clauses.

Academic writing uses restrictive clauses to narrow research scope: “Studies that examined participants over 65 showed different results.” The age restriction is essential—the sentence isn’t about all studies, just those with elderly participants.

Technical documentation depends on restrictive modifiers: “The procedure that produces the best results requires three steps.” This identifies which specific procedure you should follow, not just any procedure.

Creative writing employs them for specificity: “The house that stood on the corner was demolished.” This tells readers which house, establishing a specific location in the narrative.

News articles use restrictive modification for precision: “Companies that violate the regulation face fines up to $50,000.” This clarifies consequences apply only to violators, not all companies.

Incorrect Usage and Corrections

❌ “The book, that I recommended, is out of print.” (commas make it non-restrictive)

✅ “The book that I recommended is out of print.” (correctly restrictive, no commas)

❌ “People, who exercise daily, live longer.” (suggests all people live longer)

✅ “People who exercise daily live longer.” (correctly specifies which people)

❌ “The documents, which contain errors, need revision.” (implies all documents have errors)

✅ “The documents that contain errors need revision.” (only error-containing documents)

❌ “Software which crashes frequently should be replaced.” (using “which” suggests non-restrictive in American English)

✅ “Software that crashes frequently should be replaced.” (American English prefers “that”)

❌ “The employee, who handles complaints, is on vacation.” (treats role as extra info)

✅ “The employee who handles complaints is on vacation.” (role is identifying information)

Context Variations

Professional emails benefit from restrictive precision: “Please review the files that require your signature by Friday.” This specifies which files need attention, preventing confusion about whether all files need review.

Academic papers use restrictive clauses to define methodology: “We analyzed samples that showed contamination levels above 50 ppm.” The threshold is essential—it defines which samples the analysis included.

Business proposals employ restrictive modification strategically: “We recommend solutions that reduce costs by at least 15%.” This commits to specific performance levels rather than general cost reduction.

When training junior editors, I emphasize testing whether information is essential. Ask: “Does this modifier tell me which specific one?” If yes, it’s restrictive. No commas.

Restrictive vs Non-Restrictive Modifiers: What’s the Difference?

The fundamental difference is whether the information is essential for identification. Restrictive modifiers provide necessary identifying details. Non-restrictive modifiers add bonus information about something already identified.

Restrictive example: “The teacher who taught chemistry retired.” The clause identifies which teacher by their subject.

Non-restrictive example: “Mrs. Johnson, who taught chemistry, retired.” Mrs. Johnson is already identified by name, so her subject is extra information.

Comma usage marks the distinction. Restrictive modifiers never take commas. Non-restrictive modifiers always require commas (or dashes) to set them off from the main sentence.

Meaning changes depending on restriction status. “My brother who lives in Boston called yesterday” (restrictive) implies I have multiple brothers, and I’m specifying the Boston one. “My brother, who lives in Boston, called yesterday” (non-restrictive) implies I have one brother, and his Boston residence is additional information.

The pronoun “that” versus “which” helps in American English. “That” typically signals restrictive clauses about things. “Which” typically signals non-restrictive clauses. British English uses “which” for both, making punctuation the sole marker.

This distinction causes frequent errors in business writing. Consider: “The report that was submitted late will be reviewed tomorrow” versus “The report, which was submitted late, will be reviewed tomorrow.” The first identifies which report by its late submission. The second mentions lateness as an aside about an already-identified report.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

| Mistake | Example | Why It’s Wrong | Correction |

| Adding commas to restrictive clauses | ❌ “Dogs, that bark loudly, disturb neighbors.” | Commas signal non-essential info | ✅ “Dogs that bark loudly disturb neighbors.” |

| Removing commas from non-restrictive | ❌ “My car which is red is parked outside.” | Missing commas confuse meaning | ✅ “My car, which is red, is parked outside.” |

| Using “which” restrictively in American English | ❌ “The solution which works best costs more.” | “Which” suggests non-restrictive | ✅ “The solution that works best costs more.” |

| Separating modifier from noun | ❌ “The policy is outdated that governs overtime.” | Distance creates confusion | ✅ “The policy that governs overtime is outdated.” |

| Treating names as restrictive | ❌ “John Smith who works here resigned.” | Names are already specific | ✅ “John Smith, who works here, resigned.” |

Writers most commonly add commas where they shouldn’t, treating restrictive information as if it’s optional. This happens when authors pause naturally while reading and insert commas at pause points rather than grammatical boundaries. Reading aloud doesn’t reliably indicate comma placement—grammar rules do.

The “which” versus “that” confusion persists because British English allows both. American writers should default to “that” for restrictive clauses about things: “The method that works” not “The method which works.”

Position errors occur when writers separate modifiers from their nouns. Keep restrictive elements immediately after what they modify: “The data that supports this conclusion” not “The data is convincing that supports this conclusion.”

Visualizing the Difference

The visual shows how commas literally set off non-restrictive elements from the sentence core, while restrictive elements integrate seamlessly. Think of commas as parentheses—they signal “here’s some extra information” rather than “here’s necessary identifying information.”

This visual representation helps when editing. If you can imagine parentheses around the clause without changing which noun you’re discussing, it’s non-restrictive and needs commas. If parentheses would make the noun unclear, it’s restrictive and should have no commas.

Why We Call Them “Restrictive”

The terminology comes from the modifier’s function: it restricts or narrows the noun’s meaning to a specific subset. Linguistically, “restrict” means to limit or confine to particular boundaries.

When you say “books that I own,” you’re restricting the category “books” to only those you personally own—excluding all other books. The modifier creates boundaries around which members of the category you mean.

This contrasts with “books, which I enjoy reading,” where the clause doesn’t restrict which books. Instead, it adds commentary about an already-identified group. The term “non-restrictive” reflects this lack of limiting function.

The grammatical terminology emerged as linguists formalized English grammar rules in the 19th and early 20th centuries. They needed terms to distinguish between modifiers that narrow meaning (restrictive) versus those that expand on already-clear meaning (non-restrictive).

Understanding the “why” behind the name helps writers remember the function. Restrictive = restricts to specific members. Non-restrictive = doesn’t restrict, just adds information.

How Do You Remember the Rule?

Use the “essential information” test. Ask yourself: “Can I remove this modifier without changing which specific thing I’m talking about?” If removing it makes the noun unclear, it’s restrictive—no commas. If the noun is still clear without it, it’s non-restrictive—use commas.

The comma-removal trick works reliably. Read the sentence without the modifier. Does it still identify the same specific thing? If yes, the modifier is non-restrictive and needs commas. If no, it’s restrictive and gets no commas.

For American writers, remember: “that” = restrictive = no commas. This simple equation handles most situations involving things and objects.

Think of restrictive modifiers as nametags that identify which one you mean. Nametags aren’t optional extras—they’re necessary for identification. Non-restrictive modifiers are like fun facts written below the nametag—interesting but not essential.

When reviewing technical documents, I teach editors to physically bracket every modifier and ask: “Essential for ID?” If yes, remove brackets and ensure no commas. If no, convert brackets to commas.

Conclusion

Restrictive modifiers provide essential information that identifies which specific noun you’re discussing, and they never take commas. They differ from non-restrictive modifiers, which add extra but non-essential information and require comma separation.

Understanding this distinction ensures precise communication, particularly in professional, academic, and legal writing where ambiguity causes problems.

Apply the essential information test: if removing the modifier changes which specific thing you mean, it’s restrictive—no commas needed. Master this concept and you’ll write with the clarity professional contexts demand.

FAQs

A restrictive modifier is a word, phrase, or clause that provides essential information to identify which specific noun you’re discussing. It restricts the noun’s meaning to a particular subset.

No, restrictive modifiers never use commas because they provide essential identifying information that integrates into the sentence structure.

Restrictive modifiers provide essential identifying information (no commas). Non-restrictive modifiers add extra but non-essential information (require commas).

In American English, use “that” for restrictive clauses about things. British English uses “which” for both restrictive and non-restrictive clauses.

Ask: “Can I remove this modifier without changing which specific thing I’m talking about?” If removing it makes the noun unclear, it’s restrictive.

Yes, single-word restrictive modifiers (adjectives) come before nouns: “The red car” where “red” restricts which car. Clauses typically follow nouns.

You change the meaning from essential identification to optional extra information, potentially confusing readers about which noun you mean.

Most are in American English, yes. “That” typically signals restrictive clauses, which is why they don’t take commas.