Non-finite verbs are verb forms that don’t show tense, person, or number—they exist outside normal conjugation patterns. The three types of non-finite verbs are infinitives (to walk), gerunds (walking as noun), and participles (walking/walked as modifier). Unlike finite verbs that anchor complete sentences, non-finite verbs function as grammatical chameleons, acting as nouns, adjectives, or parts of complex verb phrases.

Why Does Your Brain Struggle With These Verb Forms?

Your brain stumbles over non-finite verbs because of Categorical Perception—the neurological tendency to sort grammatical elements into clean boxes. When you learned language as a child, your brain built categories: nouns name things, verbs show actions, adjectives describe. Non-finite verbs violate these boundaries.

Here’s the cognitive problem: A gerund like “running” looks identical to a present participle. Your brain must process context to determine whether “running” functions as a noun (“Running is exhausting”) or part of a progressive verb (“She is running”). This category ambiguity overloads working memory because the same word-form demands different grammatical interpretations.

The confusion deepens with infinitives. When you see “to walk,” your brain recognizes the verb “walk” but must suppress the expectation of tense marking. There’s no signal indicating past, present, or future—the form exists in grammatical limbo. As a result, learners often misuse infinitives where finite verbs belong, producing errors like “Yesterday I to walk” instead of “Yesterday I walked.”

Categorical Perception creates mental shortcuts that fail with non-finite verbs. Your brain expects verbs to conjugate and nouns to remain stable, but non-finite forms refuse both patterns.

Historical Evolution and Core Concepts

English inherited its non-finite verb system from Germanic roots, though centuries of linguistic change have simplified what were once more complex paradigms. Inflectional Morphology explains how these forms evolved by shedding the person and number markers that define finite verbs.

Etymology and Inflectional Morphology

The term “non-finite” literally means “not limited”—these verbs aren’t limited by tense, person, or number. In Old English, verbs carried extensive inflectional endings that marked grammatical relationships explicitly. As English simplified between 1100-1500 CE, many inflections disappeared, leaving non-finite forms as the bare stems.

Infinitives descended from Old English forms like “to writenne,” which eventually shortened to modern “to write.” The “to” particle derives from a directional preposition indicating purpose or goal—remnants visible in phrases like “go to work” where movement and action blend.

Gerunds emerged from Old English verbal nouns that carried the suffix “-ung” or “-ing.” These forms allowed speakers to nominalize actions, creating nouns from verbs without changing the root. Modern English preserved this pattern while dropping most other nominal suffixes.

Participles split into present and past forms, each with distinct historical origins. Present participles continued the Old English “-ende” ending, which shifted to “-ing” through phonetic erosion. Past participles preserved the “-ed” suffix for regular verbs while maintaining irregular forms like “spoken” and “written” from Old English strong verb patterns.

Grammatical Mechanics and TAM Marking

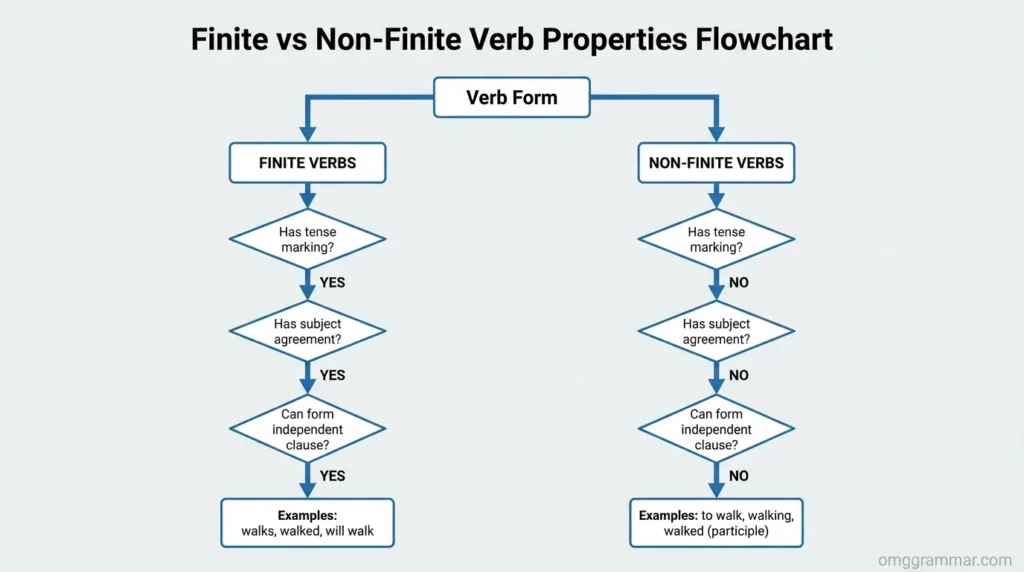

Non-finite verbs lack Tense-Aspect-Mood marking—the three grammatical dimensions that define finite verbs. This absence creates their distinctive properties and restricts where they can appear in sentences.

The Golden Rule: Non-finite verbs cannot function as the main verb in an independent clause. They need finite auxiliary verbs for tense marking or must serve as nouns, adjectives, or adverbs.

Finite verbs carry person and number agreement: “I walk” versus “she walks.” That “-s” on “walks” signals third-person singular present tense. Non-finite forms ignore this entirely—”to walk” and “walking” never change for person or number.

Tense marking separates finite from non-finite most clearly. “Walked” is finite (past tense), but “walking” remains non-finite until paired with an auxiliary: “is walking” (present progressive), “was walking” (past progressive). The auxiliary carries the tense load while the non-finite participle provides aspectual information.

Mood marking also distinguishes these categories. Finite verbs can express subjunctive mood (“If I were rich”), but non-finite forms can’t. You cannot say “to were” or “being were”—the subjunctive requires finite conjugation.

How Non-Finite Verbs Function in Real Contexts

Understanding proper usage requires seeing how non-finite verbs operate across professional and casual writing. The distinction matters because misusing these forms creates grammatical errors that undermine clarity.

Formal Academic and Professional Usage

In formal writing, non-finite verbs appear in three dominant patterns: infinitive phrases expressing purpose, gerund phrases as subjects or objects, and participial phrases as modifiers. Each serves distinct rhetorical functions that finite verbs cannot fulfill.

Example: “To understand non-finite verbs requires careful analysis of their syntactic behavior.” The infinitive phrase “to understand non-finite verbs” functions as the subject of “requires.” No finite verb can occupy this position—you cannot write “Understanding understood non-finite verbs requires analysis.”

Professional writing exploits non-finite verbs for sentence compression. Instead of writing “When I was walking to work, I noticed the construction,” skilled writers use “Walking to work, I noticed the construction.” The participial phrase “walking to work” eliminates the finite “was” without sacrificing clarity.

Active voice dominates in these constructions: “Hoping to improve results, researchers redesigned the experiment” rather than “Results were hoped to be improved through experimental redesign.” The non-finite “hoping” preserves agency while avoiding passive voice bloat.

Casual Conversational Contexts

Text messages and informal emails frequently feature non-finite verbs in compressed structures. “Running late, be there in 10” drops the finite auxiliary “am” that formal grammar demands. The bare participle “running” conveys progressive aspect without explicit tense marking.

Social media posts push this compression further: “Loving this new coffee shop!” uses the gerund-like present participle without a finite verb. Strict grammarians reject this as a sentence fragment, but conversational English accepts it because context supplies the missing elements.

The tone shift between formal and casual usage isn’t about the non-finite verbs themselves but about syntactic completeness. Casual contexts tolerate fragments; professional writing demands full clauses with finite anchors.

The Nuance Trap: When Grammar and Clarity Clash

Sometimes grammatically correct non-finite verb usage sounds awkward or unclear. You might write “Having been written by committee, the report lacked coherence,” which is technically correct but stylistically clunky. The passive perfect participle “having been written” creates excessive complexity.

Native speakers often prefer finite alternatives: “The committee wrote the report, but it lacked coherence.” This version uses finite “wrote” and “lacked,” avoiding the participial construction entirely. Grammatical correctness doesn’t guarantee readability.

Conversely, some non-finite constructions sound more natural than finite alternatives. “I enjoy swimming” flows better than “I enjoy that I swim.” The gerund “swimming” fits English rhythm patterns more comfortably than the finite clause alternative.

Non-Finite Verbs in Literature and Academic Discourse

Classic literature demonstrates how skilled writers manipulate non-finite verbs for stylistic effect. Modern academic writing has developed its own conventions around these forms.

Classic Literature

Jane Austen’s “Pride and Prejudice” (1813) features participial phrases that create elegant sentence structures. Her opening line uses finite verbs exclusively, but subsequent sentences employ participles for descriptive economy: “A single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife”—here “in possession” functions as a participial phrase modifying “man.”

Modern Stylistic and Academic Usage

Contemporary academic writing exploits non-finite verbs for hedging and precision. Researchers write “To determine significance, we conducted a chi-square test” rather than the more verbose finite alternative. The infinitive “to determine” efficiently expresses purpose without requiring a full subordinate clause.

Scientific papers favor participial phrases for methodological descriptions: “Using a double-blind protocol, researchers eliminated bias.” The present participle “using” provides temporal and causal information while maintaining active voice and sentence compression.

Style guides in 2026 increasingly recommend limiting stacked non-finite phrases. A sentence like “Having been designed to measure outcomes influenced by external variables requiring careful control” creates processing difficulty despite grammatical correctness. Modern writing standards prefer breaking such constructions into multiple sentences with finite verbs.

Synonyms and Distinguishing Non-Finite Forms

Understanding semantic and functional alternatives helps clarify when to use each non-finite verb type and what distinguishes them from related constructions.

Semantic Neighbors and Functional Alternatives

Non-finite verbs don’t have direct synonyms because they represent grammatical categories rather than lexical items. However, functional alternatives exist:

For infinitives expressing purpose:

- In order to + verb: More explicit purpose marking

- For the purpose of + gerund: Nominal alternative

- So that + finite clause: Finite purpose construction

Each alternative shifts the semantic frame. “To improve” emphasizes intended outcome, while “so that we improve” emphasizes conditional relationship.

For gerunds as subjects:

- The act of + gerund: More formal nominalization

- Noun form: Direct nominal equivalent where available

- That-clause: Finite nominal clause

“Swimming is healthy” versus “The act of swimming is healthy” versus “That one swims is healthy.” The gerund provides the most concise option.

For participles as modifiers:

- Relative clause: Finite alternative with explicit subject

- Adjective: When available for the concept

- Prepositional phrase: Different structural solution

“The running water” versus “the water that runs” versus “the flowing water.” Each construction emphasizes different aspectual properties.

Visualizing the TAM Marking Difference

This visualization clarifies why non-finite verbs behave differently from finite counterparts. The absence of TAM marking creates distinct syntactic distribution patterns.

Regional Variations: US vs UK

Both American and British English use identical non-finite verb forms with minimal variation. The only difference involves gerund versus infinitive preference after certain verbs. British English slightly prefers “I enjoy to swim” constructions that American English rejects in favor of “I enjoy swimming.”

However, this preference affects finite verb choice (which verb patterns allow infinitive complements) rather than the non-finite forms themselves. The infinitive “to swim” and gerund “swimming” function identically across all English varieties.

Australian English follow British patterns generally but show American influence in technical and academic writing. Canadian English tracks American usage almost completely for non-finite verb distribution.

Common Mistakes People Make

Five errors dominate non-finite verb usage. Each stems from the categorical perception issues discussed earlier, where learners misapply finite verb expectations to non-finite contexts.

| Incorrect | Correct | The Fix |

| “I want going to the store.” | “I want to go to the store.” | After “want,” use infinitive (to + verb), not gerund. Different verbs take different complements. |

| “She enjoys to read novels.” | “She enjoys reading novels.” | After “enjoy,” use gerund (-ing), not infinitive. The verb “enjoy” requires gerund objects. |

| “To walking is good exercise.” | “Walking is good exercise.” OR “To walk is good exercise.” | Don’t mix infinitive “to” with gerund “-ing.” Use one form or the other. |

| “Having saw the movie, I left.” | “Having seen the movie, I left.” | Perfect participles require past participle form (“seen”), not simple past (“saw”). |

| “The man to drive the car is skilled.” | “The man driving the car is skilled.” | Use present participle for restrictive modification, not infinitive. |

The psychological trigger behind these errors involves overgeneralization. Learners acquire one pattern (“want to go”) and incorrectly extend it to verbs requiring different complements (“enjoy reading”). This reflects how the brain builds grammatical rules through pattern extraction.

Another trigger: interference from other languages. Spanish speakers often produce infinitive errors because Spanish uses infinitives where English requires gerunds. “Me gusta nadar” (I like to-swim) transfers as “I like to swim,” which happens to work, but “disfruto nadar” transferred as “I enjoy to swim” fails because English “enjoy” requires gerunds.

Categorical Perception amplifies these problems. Once learners categorize certain verbs as “taking infinitives,” they resist learning exceptions. The brain prefers consistent categories even when language presents irregular patterns.

Practical Tips and Field Notes

Mastering non-finite verbs requires both understanding the grammatical principles and developing recognition patterns through practice. These field-tested techniques help cement the distinctions.

The Editor’s Field Note

In 2015, while editing a doctoral dissertation in linguistics, I caught a systematic error that had persisted through three draft revisions. The student had written “The researcher’s goal was understanding non-finite verb acquisition” throughout a 300-page manuscript. The correct form should have been either “to understand” (infinitive of purpose) or “the understanding of” (nominalized gerund).

The revision process was intense. Red digital markup covered every chapter as I flagged each instance, explaining why the construction failed. We sat in her cramped office, dissertation printouts scattered across her desk, as I explained that “understanding” as a bare gerund couldn’t follow “was” without an article or possessive marker.

That experience taught me something critical about non-finite verbs: advanced speakers make errors not from ignorance but from incomplete pattern recognition. The student knew gerunds and infinitives theoretically but hadn’t internalized when each structure worked idiomatically. After that session, I developed a habit of checking every “be + -ing” construction in manuscripts—if it lacks a clear auxiliary relationship, it probably needs revision.

Mnemonics and Memory Aids

Try this mnemonic for remembering non-finite categories:

“I GIve you Perfect forms— Infinitive, Gerund, Participle.”

Or use this visualization: Picture non-finite verbs as frozen verbs—they’re locked without tense markers, waiting for finite auxiliaries to “thaw” them into time.

Another method: Remember the three questions non-finite verbs can’t answer:

- “When?” (No tense)

- “Who?” (No person/number)

- “Alone?” (Can’t form independent clauses)

Associate infinitives with purpose using “TO DO something.” Associate gerunds with nouns using “-ING things.” And associate participles with modifiers using “-ING/-ED descriptions.”

Conclusion

The distinction between finite and non-finite verbs isn’t academic trivia—it’s the foundation of English sentence structure. Non-finite verbs lack tense, person, and number marking, which prevents them from anchoring independent clauses but allows them to function as nouns, adjectives, and parts of complex verb phrases.

Remember that the three types—gerunds, infinitives, and participles—each serve distinct grammatical roles. Infinitives express purpose and follow certain verbs. Gerunds nominalize actions. Participles modify nouns and form progressive/perfect verb phrases.

FAQs

Non-finite verbs are verb forms that lack tense, person, and number marking. The three types are infinitives (to walk), gerunds (walking as noun), and participles (walking/walked as modifiers). They cannot function as main verbs in independent clauses.

Finite verbs show tense and agree with subjects; non-finite verbs don’t. Finite: “She walks” (present tense, third person). Non-finite: “to walk,” “walking” (no tense, no agreement).

No. Non-finite verbs must pair with finite auxiliaries or function as nouns/modifiers. “Walking” alone isn’t a sentence; “I am walking” works because “am” is finite.

Check for tense and subject agreement. If the verb doesn’t change for past/present/future or for different subjects, it’s non-finite.

Infinitives (to + verb), gerunds (-ing as noun), and participles (-ing or -ed as modifier/verb phrase component).

No. Many languages lack distinct non-finite forms. English, Latin, and Sanskrit have them; Chinese and some other languages don’t make this distinction.

It depends on the main verb. “Want” takes infinitives (“want to go”). “Enjoy” takes gerunds (“enjoy going”). You must learn which verbs prefer which complements.

No, not grammatically. Every complete sentence needs at least one finite verb.

A participle showing completed action before another time: “having walked,” “having eaten.” It combines “having” with a past participle.

They have identical forms (-ing) but different functions.