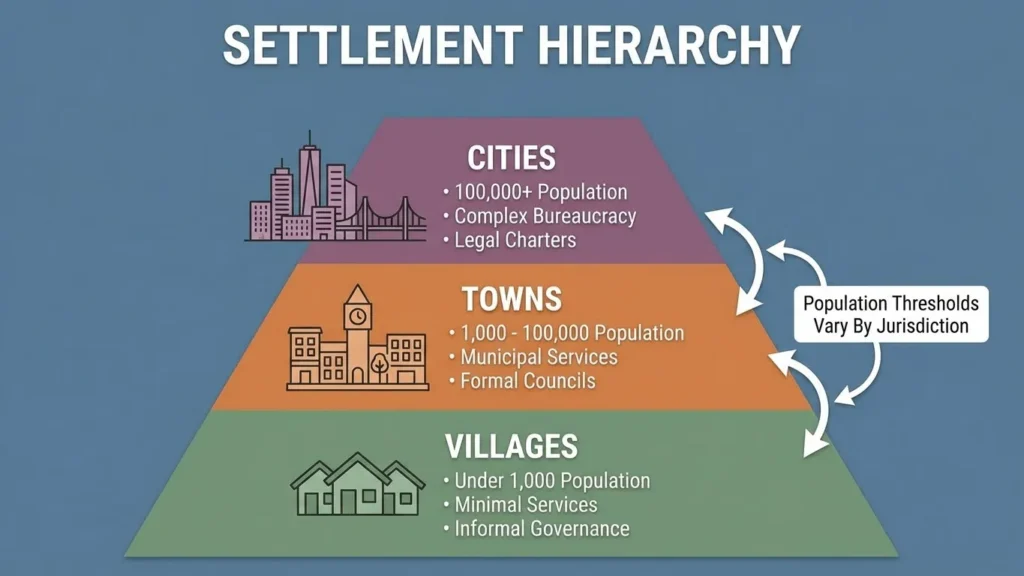

City vs Town vs Village: The difference between city, town, and village depends on legal status, population size, and administrative infrastructure—not just headcount. A city typically holds a legal charter or cathedral, populations exceeding 100,000, and complex governance structures. Towns range from 1,000 to 100,000 residents with basic municipal services. Villages contain fewer than 1,000 people with minimal formal administration.

Why These Three Words Confuse

You drive through a settlement with 15,000 people. The sign says “Town of Riverside.” Two miles away, another settlement with 12,000 people calls itself “Riverside City.” Your brain short-circuits. Which one is lying?

Neither. Your confusion stems from categorical perception—your brain wants clean boundaries between concepts. “Small,” “medium,” and “large” feel natural. But city, town, and village exist on a continuum with fuzzy edges, and legal definitions override population logic. That’s where categorical perception fails you. Your brain evolved to categorize predators from prey, not administrative jurisdictions from census data.

Scalar ambiguity compounds the problem. Unlike “child vs adult” (which has a legal age threshold), settlement classifications shift by country, state, and historical precedent. What qualifies as a city in Wyoming (population threshold: 4,000) would be a village in California. Your brain searches for universal rules. None exist. The confusion isn’t your fault—it’s built into the system.

Core Concepts and Historical Evolution

Settlement classifications emerged from medieval European legal systems where charters, cathedrals, and market rights—not population—determined status. Cities gained privileges through royal or ecclesiastical decree. Towns earned market charters allowing trade. Villages remained agricultural clusters without formal legal recognition.

Etymology and Charter Systems

“City” descends from Latin civitas (citizenship, community), which Romans used for settlements with political rights and defensive walls. The word carried legal weight—a civitas wasn’t just big; it held juridical authority. When Germanic tribes borrowed the term (Old English cirice evolved separately for “church”), they preserved this status distinction.

“Town” traces to Old English tun (enclosure, homestead), related to Proto-Germanic tunaz (fence). Originally, a tun meant any fenced settlement. Over centuries, it specialized to mean a settlement larger than a village but lacking city privileges. By 1200 CE, English law distinguished “market towns” (holding trade charters) from agricultural villages.

“Village” entered English from Old French village (around 1300 CE), itself from Latin villaticus (farm estate). Romans used villa for country estates worked by villani (peasants). The term always signaled rural, agricultural, and small—the opposite of urban civitas.

Medieval borough formation codified these distinctions legally. A city needed a royal charter or bishop’s seat. Towns required market rights granted by the Crown. Villages had neither—they existed under manorial jurisdiction, governed by local lords rather than municipal councils. This tripartite system spread across Europe and European colonies, creating classification frameworks that persist into 2026.

Administrative Nomenclature and Legal Mechanics

Modern usage follows administrative nomenclature rules, not population formulas. In the United States, each state legislature defines what constitutes a city versus a town. Montana law designates any incorporated settlement as a “city” regardless of size—so Montana has “cities” with 200 residents. Massachusetts distinguishes between “cities” (chartered) and “towns” (town-meeting governance), regardless of population.

Golden Rule: Settlement classification depends on legal incorporation status and governance structure first, population second, and cultural usage third.

This creates paradoxes. Arlington, Virginia (population 238,000) remains legally a “county” with no municipalities—residents live in an unincorporated area. Meanwhile, Vernon, California (population 110) operates as a legally incorporated city with a mayor and city council. The classification reflects legal structure, not headcount.

Proper noun classification adds another layer. “New York City” requires capitalization as an official designation. “The city of Denver” uses lowercase “city” as a common noun descriptor. When “city” appears in official names (Kansas City, Oklahoma City), it functions as part of the proper noun. When it describes a place generically (“I live in a small city”), it’s a common noun requiring no capitals.

How Population Thresholds Differ Globally

No universal population standard exists—thresholds vary by country and change over time based on urbanization rates. What counts as a city in rural regions might be a village in densely populated areas.

United Kingdom Standards

The UK traditionally granted city status through royal charter, not population. St Davids, Wales (population 1,600) holds official city status because it has a cathedral. Meanwhile, Reading (population 318,000) remained a town until 2022, when it finally received city status during Queen Elizabeth II’s Platinum Jubilee.

British towns typically range from 5,000 to 100,000 residents. Villages fall below 5,000. But these are cultural norms, not legal requirements. A settlement with 3,000 people might call itself a town if it has urban characteristics (shops, services, paved roads), while another with 4,000 might remain a village if it’s primarily agricultural.

United States Framework

American definitions splinter into 50 state systems. New York State requires 50,000 residents for city incorporation. California sets no minimum—Amador City (population 200) is California’s smallest incorporated city. Texas allows any settlement to incorporate as a city once it reaches 200 residents.

The U.S. Census Bureau uses “urbanized areas” (50,000+ people) and “urban clusters” (2,500-50,000) for statistical purposes, but these don’t determine legal city status. A settlement could be an “urbanized area” statistically while remaining unincorporated legally.

International Variations

Denmark classifies settlements over 200 as towns. Japan requires 50,000 for city status. India uses “statutory towns” (places with municipal corporations) versus “census towns” (urban characteristics but no formal governance), creating a dual system. Australia abandoned legal distinctions—”city” now describes large urban areas informally, while local government areas use names like “City of Melbourne” as administrative titles regardless of size.

Contextual Examples Across Settlement Types for City vs Town vs Village

Classification manifests differently in formal documents versus casual speech, and context determines which term fits best. Legal precision matters in official use; cultural norms dominate everyday conversation.

Formal and Administrative Usage

Official documents demand precision. A zoning application might state:

The proposed development sits within the incorporated city limits of Springfield, adjacent to the unincorporated town of Riverside.

Subject: “The proposed development” | Verb: “sits” | Object: prepositional phrase establishing jurisdiction.

“Incorporated city” signals legal status—Springfield has a city charter. “Unincorporated town” indicates Riverside lacks formal municipal government but functions as a named settlement. Using “town” instead of “village” suggests size (likely 2,000+ residents). The distinction matters legally—building codes differ between incorporated and unincorporated areas.

Legal contracts specify settlement types to establish jurisdiction. “The property located in the Village of Oakmont, County of Lancaster” identifies which municipal code applies. Swap “village” for “city,” and you’ve potentially referenced the wrong legal entity.

Casual and Conversational Contexts

In everyday speech, people default to cultural norms:

“I grew up in a small town in Ohio—maybe 8,000 people.”

The speaker uses “town” because 8,000 feels mid-sized, even if the place legally incorporated as a city. Americans rarely say “I’m from a village” unless describing European or rural developing-world settlements. “Village” carries old-fashioned or foreign connotations in modern American English.

British speakers use “village” more freely: “I live in a lovely village in the Cotswolds” sounds natural, not archaic. The same settlement described by an American might become “a small town.” Cultural linguistic patterns override legal definitions in casual contexts.

The Nuance Trap

Here’s where people stumble: matching official designation to conversational expectations. If you’re from Vernon, California (population 110, legally a city), saying “I’m from a city” sounds absurd. You’d say “a small town” to match listener expectations, even though you’d be technically wrong.

Conversely, residents of large towns approaching city-size populations (like Reading, UK before 2022) often called their home “the city” colloquially, despite lacking official status. They weren’t wrong culturally—just legally imprecise.

Settlement Classifications in Literature

Classic texts reveal how city, town, and village carried distinct social meanings beyond mere size—cities meant opportunity and anonymity, towns meant community and commerce, villages meant tradition and isolation.

Classic Literature Analysis

Thomas Hardy’s The Mayor of Casterbridge (1886) opens with the line describing Casterbridge as “a borough” and “county-town,” using “town” despite the settlement’s significant size and economic importance. Hardy chose “town” over “city” deliberately—it positioned Casterbridge as provincial, not metropolitan. The word signaled readers should expect tight-knit social networks where reputation mattered, unlike the anonymity of cities like London.

Charles Dickens contrasted city and village throughout his works. In Great Expectations (1861), Pip’s marshland village represents backward rurality, while London embodies cosmopolitan corruption. Dickens used “village” to evoke smallness, ignorance, and agricultural labor. “City” meant industry, sophistication, and moral danger.

Jane Austen’s novels consistently use “town” for Bath and London—places characters visited for the social season. “Village” described places like Highbury (in Emma, 1815), where everyone knew everyone and social circles constrained choice. Settlement type dictated plot possibilities: villages forced characters into limited social interactions, cities enabled escape and reinvention.

Modern Urban Planning Context

Contemporary urban planning discussions use these terms with technical precision. “Satellite towns” describe settlements within metropolitan areas that maintain separate governance. “Edge cities” refer to suburban commercial centers that function as cities economically but lack legal city status. “Urban villages” means mixed-use developments designed to mimic village walkability within cities.

Planners distinguish “towns” (independent municipalities) from “suburbs” (bedroom communities dependent on nearby cities). The 2020s saw renewed interest in “15-minute cities”—urban design where residents access necessities within fifteen minutes by foot or bike. This concept applies to cities and towns but rarely villages, which lack service density.

Synonyms and Regional Terminology

Settlement classification synonyms carry cultural baggage—”hamlet,” “borough,” and “municipality” signal different governance models and historical contexts.

Semantic Neighbors

“Hamlet” describes settlements smaller than villages—typically under 100 residents, no church or services. The term survives primarily in British English and historical contexts. Americans rarely use it outside academic or historical discussion.

“Borough” in the UK means a town with corporate privileges or parliamentary representation. In New York City, “borough” describes administrative divisions (Manhattan, Brooklyn). In Alaska, a “borough” functions like a county. Same word, radically different meanings across jurisdictions.

“Municipality” serves as the umbrella term—any settlement with formal government qualifies. Cities, towns, and some villages are municipalities. The term emphasizes legal structure over size. “Incorporated municipality” specifies legal incorporation, distinguishing it from unincorporated settlements.

Visualizing Settlement Hierarchy: City vs Town vs Village:

Regional Variations

British English maintains stricter distinctions. “Village” remains common for small settlements. “Town” describes market towns. “City” requires historical charter or cathedral. Americans blur these—”small town” might describe what Brits call a village.

Australian English largely abandoned formal distinctions. “City” appears in official names (City of Sydney) but describes large urban areas informally. New Zealanders follow similar patterns, using “town” broadly for anything between village and city size.

Common Mistakes and Classification Errors of City vs Town vs Village

People make predictable errors when labeling settlements, usually by over-relying on population while ignoring legal and cultural factors.

| Incorrect | Correct | The Fix |

| “Any place over 10,000 is a city” | Cities require legal incorporation or charter | Check legal status, not just population |

| Using “village” for American suburbs | Most suburbs are incorporated towns or cities | “Village” implies rural character in US English |

| Capitalizing “city” in “the city of Boston” | Lowercase unless part of official name | “City” is a common noun here, not proper |

| Assuming UK and US definitions match | Each country uses different criteria | Learn jurisdiction-specific rules |

| Calling incorporated settlements “towns” when they’re legally cities | Use official designation in formal writing | Verify incorporation documents |

The psychological trigger is schema rigidity—people learn a simple rule (“cities are big, towns are medium, villages are small”) and apply it universally. When reality contradicts the rule (tiny legal cities, huge unincorporated towns), cognitive dissonance results. They blame the “exception” rather than revising the overly simple schema.

Another trigger: linguistic imperialism. Americans assume “village” means “quaint European settlement” because that’s how American English uses it. They forget that billions of people worldwide live in villages and use the term neutrally. The word carries different connotations across cultures.

Practical Tips and Field Notes

When I Corrected a Journalist’s Settlement Error

In 2017, I edited a feature article for a regional magazine about growth in suburban areas. The journalist called a settlement of 47,000 people “a small village experiencing rapid expansion.” I flagged it immediately. Villages don’t have 47,000 residents—that’s solidly town territory, possibly small-city depending on the state.

I called the journalist. She insisted: “But it feels like a village—everyone knows everyone, it’s got that small-town charm.” I explained that feelings don’t override definitions. Readers would see “village” and picture 500 people, not 47,000. We compromised: “a close-knit town.” Accurate and evocative.

The deadline pressure was intense—the piece was due in six hours for the printer. I spent twenty minutes on the phone explaining the distinction, then another fifteen revising related passages where she’d misused “city” for incorporated towns. She’d assumed incorporation automatically meant city status. It doesn’t.

That experience taught me that even professional communicators confuse these terms. The stakes were low in a magazine feature, but imagine legal documents with this imprecision—zoning disputes, tax jurisdiction questions, service provision contracts. Words matter. Using them correctly prevents expensive confusion.

Memory Aids for Quick Decisions

Charter or Cathedral = City. If it’s got one, it’s likely a city historically or legally.

Market but no Cathedral = Town. Traditional towns held market rights—commercial centers between cities and villages.

Fields outnumber streets = Village. If agriculture dominates, you’re in village territory.

These aren’t ironclad rules—exceptions abound. But they work as mental shortcuts when you’re writing quickly and need to pick a word that sounds plausible.

Conclusion

City, town, and village represent legal, population, and cultural distinctions that vary by jurisdiction—no universal threshold exists, so check local definitions before labeling settlements. Cities typically require legal charters and populations exceeding 100,000, towns fall in the 1,000-100,000 range with municipal governance, and villages contain under 1,000 people with minimal administration. These categories reflect historical European frameworks that prioritized legal status over headcount, creating systems where tiny incorporated cities and massive unincorporated towns both exist.

FAQs

Cities have legal charters and large populations (typically 100,000+), towns have municipal governments and mid-range populations (1,000-100,000), and villages are small settlements (under 1,000) with minimal formal governance. Legal status often matters more than population—some legally incorporated cities have only 200 residents.

Yes. Towns gain city status through legal incorporation, population growth meeting state thresholds, or (in the UK) royal charter. England became a city in 2022 after centuries as a town.

Yes, villages contain fewer residents than towns. Villages typically have under 1,000 people, while towns start around 1,000 and extend to 100,000.

Legal incorporation status and population thresholds. Most jurisdictions require cities to exceed specific population counts (often 50,000-100,000) and hold formal charters. Some places achieve city status through historical designation regardless of size.

No. Requirements vary by jurisdiction. Montana and California allow cities with under 300 people. New York requires 50,000. The UK grants city status by royal charter, ignoring population.

Not accurately. Villages are definitionally smaller than towns. Calling a 400-person village a “town” misrepresents its size and governance structure.

Vatican City (population ~800, area 0.17 sq mi) holds this distinction as an independent city-state. Among incorporated US cities, Monowi, Nebraska (population 1) is often cited.

Historical designation or state law. Some settlements incorporated as towns before growing large and never changed their legal status. Others exist in states where “town” is the standard municipal designation regardless of size.