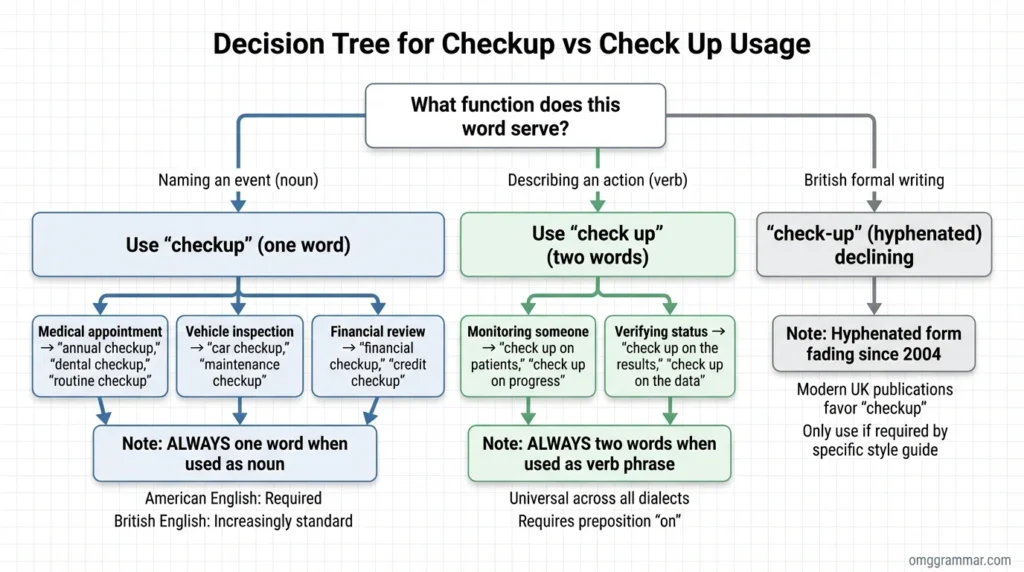

Checkup is a noun meaning an examination or inspection, while check up is a verb phrase meaning to verify or monitor something. The hyphenated form check-up was traditionally British but is declining in modern usage. In American English, “checkup” (one word) is the only correct noun form, while “check up” (two words) functions exclusively as a verb phrase with “on.”

Why Does This Simple Distinction Trip Up So Many Writers?

Your confusion makes perfect neurological sense.

When your brain encounters “checkup,” it performs morphological decomposition—automatically breaking the word into “check” and “up.” This happens within 250 milliseconds of seeing the word. Your brain recognizes both parts as independent words, so when you later see “check up” as two words or “check-up” with a hyphen, all three forms compete in your memory.

The problem intensifies because phrasal verbs like “check up” naturally convert into compound nouns like “checkup.” Your brain knows the relationship exists but struggles to remember which form serves which grammatical function. Add British versus American spelling differences, and you’ve created retrieval competition—multiple memory traces fighting for activation.

Here’s the thing: this isn’t a modern problem. English has wrestled with compound word standardization for over a century, and medical terminology adopted compound forms later than everyday vocabulary.

Core Concepts and Historical Evolution

The checkup vs check-up distinction emerged from English’s compound evolution pattern, where terms progress from open forms to hyphenated forms to closed forms, though American English accelerated this process for medical vocabulary in the early 1900s.

Etymology and Compound Evolution Pattern

The verb “check” entered Middle English from Old French “eschec” (chess), originally meaning “to verify” or “to stop.” The particle “up” derives from Old English “upp,” indicating completion or thoroughness. When combined as a phrasal verb in the 1800s, “check up” meant “to verify completely.”

The compound evolution pattern shows predictable stages. Most English compounds start as open forms with spaces. As familiarity grows, writers add hyphens to show the words function as a single unit. Eventually, frequent use leads to closed forms written as one word.

Baseball followed this exact pattern: “base ball” (1840s) became “base-ball” (1860s) and finally “baseball” (1880s). The medical term “checkup” followed a compressed version of the same journey. Early 1900s medical journals used “check up” (open) and “check-up” (hyphenated) interchangeably. By the 1920s, American medical publications standardized to “checkup” (closed) for the noun form.

British English typically moves more slowly through these stages. “Check-up” remained the British medical standard into the 1990s. However, Google Trends data shows the hyphenated form declining by 50% in UK publications since 2004. American digital media influence is accelerating British adoption of “checkup.”

Grammatical Mechanics and Phrasal Verb Conversion

Phrasal verb conversion is the process that creates compound nouns from verb phrases.

The Golden Rule: The noun is one word (checkup). The verb is two words (check up).

A phrasal verb combines a base verb with a particle (preposition or adverb) to create new meaning. “Check up” is a phrasal verb where “check” (verify) combines with “up” (completion) to mean “verify thoroughly.” This functions as an action.

When you convert a phrasal verb into a noun, you nominalize it—turn it into a thing rather than an action. The event of “checking up” becomes a “checkup.” English typically closes these conversions into single words to show they function as unified concepts. Other examples include “workout” (from work out), “setup” (from set up), and “breakdown” (from break down).

The distinction matters because nouns and verbs behave differently in sentences. As a noun, “checkup” can take articles (“a checkup,” “the checkup”) and possessives (“doctor’s checkup”). As a verb phrase, “check up” takes auxiliary verbs (“will check up,” “have checked up”) and requires prepositions like “on” to show what’s being verified.

Contextual Examples

The checkup vs check-up choice depends on whether you’re describing an event (noun) or an action (verb), with American usage requiring the closed form “checkup” for nouns.

Formal and Academic Writing

In medical and academic contexts, precision in noun versus verb usage is required.

American medical example: “The patient’s annual checkup revealed elevated blood pressure requiring immediate intervention.” This uses “checkup” as a noun modified by “annual.” The closed form signals American medical writing standards, where the noun represents a specific type of medical event.

British medical example (declining): “The practice recommends a routine check-up every six months for patients over sixty.” British medical publications traditionally used the hyphenated “check-up” as a noun, but this form is fading. Modern British journals increasingly adopt “checkup” to match international scientific conventions.

Verb phrase example: “The nurse will check up on surgical patients every four hours throughout the night shift.” Here, “check up” functions as a verb phrase with “on” introducing the object. The two-word form is universal across all English dialects.

Casual and Conversational

In everyday communication, noun and verb forms distinguish actions from events.

Noun usage (American): “I’m late because my dentist checkup took longer than expected.” The speaker describes a completed event using “checkup” as a countable noun.

Verb phrase usage (Universal): “Can you check up on the kids while I run to the store?” This requests an action. The speaker asks someone to verify the children’s status. “Check up” requires “on” to complete its meaning.

Common error: “I need to schedule a check up.” This incorrectly uses the two-word verb form where the one-word noun “checkup” is required. The sentence should read: “I need to schedule a checkup.”

The Nuance Trap

Some writers think adding a hyphen makes compound nouns more proper or formal. This is wrong.

In American English, “check-up” with a hyphen is simply incorrect as a noun. It’s not a style choice or formality marker—it’s an error. American style guides (AP, Chicago, APA, AMA) unanimously specify “checkup” (one word) for the noun.

British writers face more complexity. While “check-up” was historically standard, continuing to use it in 2026 signals resistance to global standardization. Most international journals now require “checkup” regardless of the author’s nationality. The hyphenated form survives mainly in older British publications and conservative institutional writing.

The real sophistication lies in knowing that “checkup” is always a noun, “check up” is always a verb phrase, and mixing them breaks grammatical rules, not just style preferences.

How Writers Have Used These Spellings in Medical Literature

Early 20th-century medical writers used varied forms for this emerging professional term, reflecting the compound evolution pattern before standardization took hold.

Classic Literature

Medical journals from the pre-standardization era show both “check up” and “check-up” appearing as the terminology entered professional use.

The Journal of the American Medical Association — Various Authors — 1920

“The physician should check up on the patient’s cardiac function before authorizing strenuous activity.” This shows the verb phrase usage, asking doctors to verify patient status before treatment decisions.

British Medical Journal — Various Authors — 1925

“A thorough check-up of returning soldiers revealed widespread respiratory complaints requiring long-term care.” British medical writing adopted the hyphenated noun form earlier than American publications, showing the trans-Atlantic spelling divergence that would persist for decades.

Both examples demonstrate that medical professionals needed new terminology for systematic health examinations. The verb phrase came first (check up = verify thoroughly), and the noun form emerged to describe the examination event itself.

Modern Stylistic Usage

In contemporary health writing, authors use the term to convey preventive care concepts. An American health columnist might write: “Your annual checkup isn’t just paperwork—it’s the frontline defense against silent killers like hypertension and diabetes.”

A British wellness blogger transitioning to modern standards could write: “Skipping your checkup saves an hour today but risks months in hospital tomorrow.” The one-word form shows alignment with international medical terminology.

Both examples use “checkup” as a concrete noun representing a specific medical event while emphasizing its importance in preventive healthcare strategies.

Synonyms and Variations

The checkup vs check-up distinction exists within a broader family of medical and inspection terminology where form-to-function relationships matter.

Semantic Neighbors

Examination refers broadly to any detailed inspection. Doctors conduct examinations. The term lacks the routine, preventive connotation of “checkup.” You schedule a checkup when healthy. You undergo an examination when symptoms appear.

Physical (or “physical exam”) specifically describes the hands-on inspection component. A physical is one part of a complete checkup, which may also include lab work and imaging. The terms overlap but aren’t interchangeable.

Inspection applies more to mechanical systems than health. Cars get inspections. Humans get checkups. Using “inspection” for medical appointments sounds clinical and dehumanizing.

Screening focuses on testing for specific conditions. Breast cancer screening is narrower than a wellness checkup. Screenings are components of comprehensive checkups.

The phrasal verb conversion that created “checkup” from “check up” doesn’t change these semantic relationships. However, morphological decomposition—your brain’s automatic word-breaking process—can create confusion when the compound appears in different forms across these related terms.

Visualizing the Difference

Decision flowchart showing three paths for checkup usage—one-word noun checkup for all appointments and events, two-word verb phrase check up for all action descriptions requiring on preposition, and declining hyphenated form check-up limited to traditional British formal contexts but fading in modern usage]

Regional Variations

United States: “Checkup” (one word) is the only acceptable noun form. Using “check-up” or “check up” as a noun is an error, not a style variation.

United Kingdom: Traditionally preferred “check-up” (hyphenated) but rapidly shifting to “checkup” (closed). Medical journals and scientific publications now predominantly use the American closed form. Conservative British newspapers still occasionally use the hyphen.

Canada: Follows American convention. “Checkup” (one word) is standard for nouns in Canadian medical and professional writing.

Australia and New Zealand: Historically followed British “check-up” but trending toward “checkup” in professional contexts. Informal writing may still use hyphens.

International medical standards increasingly require “checkup” regardless of the author’s origin. The World Health Organization and major medical journals use the closed form exclusively.

Common Mistakes

Writers make predictable errors with checkup vs check-up because they confuse noun and verb forms or apply outdated British conventions.

| Incorrect | Correct | The Fix |

| “I need a check up for my allergies.” | “I need a checkup for my allergies.” | Use the one-word noun “checkup” when naming the medical event |

| “The doctor will checkup on your progress.” | “The doctor will check up on your progress.” | Use the two-word verb phrase “check up” for actions; add “on” |

| “Schedule a check-up appointment.” (US writing) | “Schedule a checkup appointment.” | Drop the hyphen in American English; it’s outdated |

| “I’m going to check up the test results.” | “I’m going to check up on the test results.” | Phrasal verb “check up” requires preposition “on” |

| “My annual physical checkup.” | Either “My annual physical” or “My annual checkup” | Don’t combine “physical” and “checkup”; choose one |

The psychological trigger: Hyperorthography drives most errors.

Writers assume hyphenating makes compound words “more correct” or official-looking. This stems from seeing hyphenated compounds in other contexts (check-in, follow-up, well-being) and overapplying the pattern. But each compound has its own evolutionary stage. “Checkup” has reached closure. “Check-in” is still transitioning. “Well-being” stays hyphenated. No universal rule governs all compounds.

Noun-verb confusion worsens the problem. Because “check up” and “checkup” share the same root words, writers forget that form follows function. Your sentence’s grammar dictates which spelling is correct, not your preference or familiarity.

Practical Tips and Field Notes

The checkup vs check-up choice becomes automatic once you internalize the noun-versus-verb rule, but systematic verification prevents embarrassing mistakes in professional writing.

The Editor’s Field Note

In 2017, I was editing a multinational health insurance company’s policy documents—materials that would be translated into fourteen languages and distributed to three million members across North America and Europe. The medical benefits section, drafted by teams in Chicago and London, contained both “checkup” and “check-up” scattered throughout 200 pages.

When I flagged the inconsistency during the legal review meeting, the room went quiet. The Chicago team insisted “checkup” was standard. The London team defended “check-up” as proper British English. Both sides had supporting style guides. The legal team worried that inconsistent terminology could create coverage ambiguities—if “checkup” and “check-up” appeared in different policy clauses, members might argue they were different services.

Here’s what we decided: American policyholders would receive versions using “checkup.” British and European policyholders would receive versions using “check-up” where legally required by local medical terminology standards, but “checkup” elsewhere to match WHO conventions. The legal contracts used “checkup” universally because U.S. insurance regulations governed the master policy.

Details from that conference room still linger: the stack of competing style guides, the insurance lawyer’s warnings about litigation risk, the translator’s concern about compounding errors across languages. That’s when I learned that compound word choices aren’t just grammatical—they’re legal, financial, and cross-cultural decisions with real consequences.

Mnemonics and Memory Aids

The Appointment Test: If you can put “an” or “the” before it, use “checkup” (one word). You schedule “a checkup,” not “a check up.”

The Action Test: If you can add “on” after it, use “check up” (two words). You “check up on” someone, never “checkup on.”

The Up Spot: In the noun “checkup,” the “up” is stuck inside. In the verb “check up,” the “up” can float around the sentence: “check your patient up” or “check up on your patient.”

The Century Rule: One-word “checkup” = 21st century standard. Hyphenated “check-up” = 20th century fading form.

These shortcuts work because they bypass etymology and focus on immediate grammatical function. Morphological decomposition doesn’t interfere when you have a clear decision rule.

Conclusion

The checkup vs check-up split demonstrates that compound word forms follow evolutionary patterns tied to usage frequency and regional conventions.

Use “checkup” (one word) as a noun for medical appointments, vehicle inspections, or any systematic review event. Use “check up” (two words) as a verb phrase when describing the action of monitoring or verifying something. Avoid the hyphenated “check-up” in American writing; it’s outdated. In British writing, the hyphen is acceptable but declining as international standards favor the closed form.

Professional writing demands consistent application of the noun-versus-verb rule. Personal writing benefits from knowing that “checkup” signals modern, globally-aware usage while “check-up” marks you as either British-traditional or uninformed about current conventions.

The choice becomes intuitive with practice. Trust the grammatical function, check your regional audience, and remember that compounds evolve toward closure.

FAQs

Checkup (one word) is the noun; check-up (hyphenated) is a declining British variant. American English uses only “checkup” for nouns. British English is transitioning from “check-up” to “checkup” to match international standards.

One word when used as a noun (e.g., “annual checkup”). Two words when used as a verb phrase (e.g., “check up on patients”).

Americans use “checkup” (one word) exclusively for nouns. The hyphenated “check-up” is incorrect in American English.

Write “checkup” as one word when naming an examination or review. Write “check up” as two words when describing the action of verifying something.

Not in American English. The hyphenated form was traditional British usage but is fading rapidly in modern writing.

No. Correct: “I will check up on you.” The verb phrase requires two words and the preposition “on.”

Examination, physical, inspection, or screening, depending on context. None are exact synonyms; each carries specific connotations.

Health checkup (no hyphen, one word for “checkup”). American usage. British publications increasingly match this form.

American medical journals standardized to “checkup” in the 1920s. British usage maintained “check-up” until the 2000s, when global convergence began favoring the closed form.

Yes. “Checkup” is correct in formal American writing. British formal writing increasingly accepts it as standard for international publications.