Aging and ageing mean exactly the same thing but differ by region—Both spellings describe the process of growing older or becoming aged. Aging is standard in American English while ageing is standard in British English. They work as nouns, verbs, and adjectives with no difference in meaning, only in spelling rules.

Why Does Your Brain Stumble Over Aging vs Ageing?

Truth is, your confusion is brain-based, not grammar-based.

Your brain uses a system called orthographic processing to recognize words by their visual shape. When you see “aging” in one article and “ageing” in another, this system gets confused. It expects one spelling for one word. English gives you two.

If you read books and articles from different countries, your brain has stored both spellings. Now when you write, both versions compete in your memory. You pause. You second-guess. This isn’t you being dumb. Your brain is detecting a real split in how English speakers write this word.

Here’s the thing: this spelling split didn’t happen naturally. One man deliberately created it as part of his war against British spelling rules.

Core Concepts and Historical Evolution

The aging vs ageing debate started with Noah Webster’s spelling reforms between 1806 and 1828. He deliberately removed what he saw as extra letters from American English. His goal was to make it different from British spelling and easier to teach in schools.

Etymology and Webster’s Orthographic Reform

The word came from Old French “aage” (modern “âge”), which came from Latin “aetas.” English borrowed it around 1300 as “age.” By the 1400s, people started adding the suffix “-ing” to create “aging/ageing.”

For centuries, writers used both spellings randomly. No one enforced any rules. Then Webster arrived with a plan.

In 1806, Webster published his first dictionary with a bold idea: American schools needed American spellings. He removed letters he thought were unnecessary, changed “colour” to “color” and “centre” to “center.” He applied the same thinking to verbs.

When you add “-ing” to most words ending in silent ‘e,’ you drop the ‘e.’ “Make” becomes “making.” “Write” becomes “writing.” Webster said “age” should follow this pattern—so “aging” made sense. British spelling kept “ageing” to protect the soft ‘g’ sound and prevent confusion.

The change stuck in America. By 1828, Webster’s big dictionary had taught two generations of American kids to write “aging.” British publishers refused to change. Countries in the Commonwealth followed British rules. The split became permanent.

Grammatical Mechanics and Morphological Suffixation Rules

Both spellings follow acceptable grammar rules. They just apply different principles.

The Golden Rule: Choose based on your audience’s location, not your preference.

American grammar favors simple forms—drop the silent ‘e’ before adding suffixes that start with vowels. British grammar keeps the ‘e’ after soft consonants to show how to pronounce the word. Both systems are consistent. Neither is wrong.

The word works the same way in three grammar roles. As an adjective: “The aging population faces healthcare challenges.” As a noun: “Aging requires patience and grace.” And as a verb: “She is aging beautifully.”

The meaning doesn’t change. Only the spelling changes.

Contextual Examples

The choice between aging and ageing matters most when you know who will read your work. Using the wrong regional version tells readers you either don’t know the rules or don’t care about your audience.

Formal and Academic Writing

In academic writing, follow the journal’s style guide.

American academic example: “The researchers examined telomere shortening as a biomarker of accelerated aging in diabetic patients.” This sentence uses active voice (researchers examined), specific terms (telomere shortening, biomarker), and “aging” without the ‘e’ to meet American standards.

British academic example: “The study participants demonstrated varying rates of cognitive decline during the ageing process.” British scholarly writing keeps “ageing” even in modern neuroscience journals published in 2026.

Both sentences mean the same thing scientifically. The spelling just shows where the author plans to publish.

Casual and Conversational

In informal writing, your audience’s dialect determines the choice.

American text message: “My dog is aging fast—he can barely climb stairs anymore.” The compressed, emotional tone uses “aging” because American speakers write as they’ve been taught.

British WhatsApp: “Dad’s ageing has really accelerated this year. Quite worried about him.” The Commonwealth speaker naturally writes “ageing” without thinking about it.

In speech, both sound identical. Only spelling reveals the split. Voice-to-text software defaults to the user’s device language settings—American devices write “aging,” British devices write “ageing.”

The Nuance Trap

Some writers think “ageing” sounds smarter or more formal. They’re wrong.

Both spellings carry equal weight in their regions. Using “ageing” in an American medical journal doesn’t make you look smarter—it shows you didn’t check the publication’s rules. An Australian business report using “aging” doesn’t look modern—it looks careless.

True skill lies in matching the right spelling to the right audience, not picking one spelling for everything. Professional editors call this “audience awareness.” It separates good writers from amateurs.

How Writers Have Used These Spellings Across Time

Classic Literature

The New York Medical Journal — Various Authors — 1910

Medical professionals writing about geriatric care used “aging” consistently: “The study of aging in its physiological and pathological aspects demands systematic investigation.”

This quote shows that by 1910, American medical writing had standardized “aging” for professional use. The choice showed Webster’s influence on American scientific writing, which focused on consistent spelling in technical terms.

British Medical Journal — Various Authors — 1914

Across the Atlantic, British physicians wrote: “The processes of ageing in the human organism require careful clinical observation.”

British medical professionals kept “ageing” even in the same scientific contexts. This shows British medicine’s commitment to traditional spelling despite American changes. Both publications discussed the same medical phenomena using regionally correct spellings. This proves the split was only about spelling, not about the science itself.

Modern Stylistic Usage

An American novelist might write: “The aging spy knew his reflexes had slowed—each mission now carried stakes he couldn’t afford.” The American spelling fits naturally into the narrative voice.

A British psychological suspense author might write: “The ageing detective felt the case slipping through her grasp as cognitive decline began to shadow her legendary intuition.” The British spelling stays consistent with Commonwealth publishing standards while exploring the same themes.

Both examples show how regional spelling rules don’t limit creative writing—they just reflect the language environment where the author publishes.

Synonyms and Variations

The aging vs ageing choice sits within a larger family of words describing how things change over time. Each word carries slightly different meanings that your brain helps you tell apart.

Semantic Neighbors

Senescence refers only to biological aging at the cell level. Scientists use it in technical contexts like “cellular senescence,” which describes when cells stop dividing. It doesn’t work as well in everyday writing as aging/ageing.

Maturation focuses on growing toward peak function rather than decline. We say “wine matures” but “people age.” Maturation suggests getting better. Aging just means moving forward in time without judging if that’s good or bad.

Obsolescence describes when objects or systems break down. Technology becomes obsolete. Humans age. The difference matters because obsolescence implies you should replace something. Aging is natural and can’t be replaced.

The choice between aging and ageing doesn’t change these word relationships. But your brain’s word recognition system trains you to expect the same spelling throughout a single text.

Visualizing the Difference

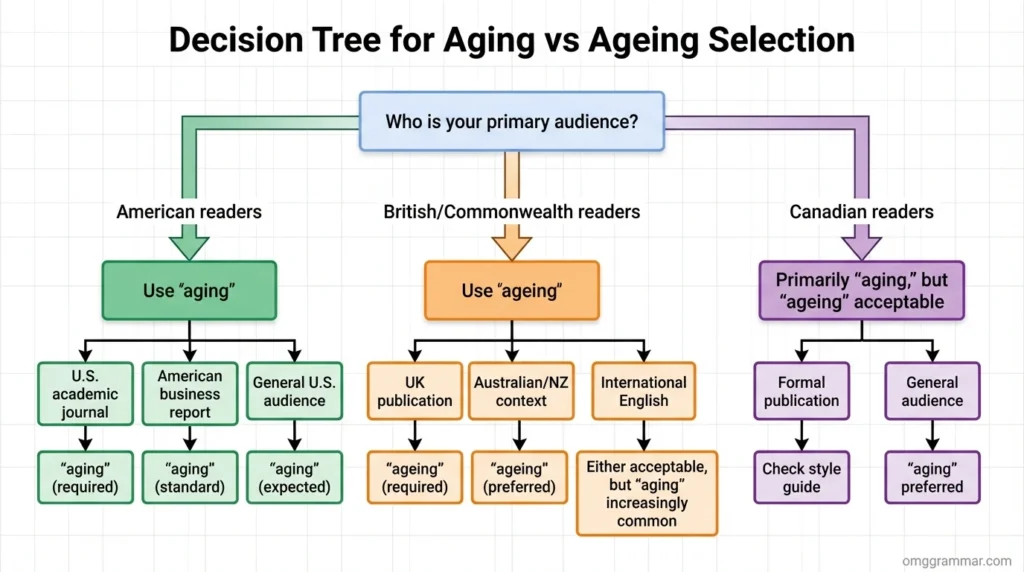

Decision tree showing selection criteria for aging versus ageing based on target audience location, with American readers requiring aging, British and Commonwealth readers preferring ageing, and Canadian contexts accepting both with aging as primary recommendation.

Regional Variations

United States: “Aging” is required in formal writing.

United Kingdom: “Ageing” stays standard in formal British English, though “aging” has gained ground in digital media where American culture has strong influence.

Canada: Canadian English officially prefers “aging” following American rules, but “ageing” appears in formal contexts with British connections.

Australia and New Zealand: “Ageing” is standard, though younger writers increasingly use “aging” because of exposure to American media.

Global digital communication has sped up the move toward “aging,” but traditional print media in Commonwealth countries still uses “ageing” as the proper form.

Common Mistakes

Writers make predictable errors with regional spelling variants. Most mistakes come from not fully understanding the rules that govern each spelling choice.

| Incorrect | Correct | The Fix |

| “The ageing population of America…” in a U.S. publication | “The aging population of America…” | Match spelling to publication geography, not subject matter location |

| “Researchers are studying aging” in Nature UK | “Researchers are studying ageing” | Check the journal’s style guide—British publications require British spelling |

| Mixing both: “The aging brain shows ageing-related decline” | Consistent use: “The aging brain shows aging-related decline” | Choose one spelling per document and maintain it throughout |

| “I prefer ageing because it looks more sophisticated” | “I use aging for American audiences, ageing for British” | Base choice on audience, not aesthetic preference |

| Using device autocorrect without verification | Manually selecting the appropriate regional variant | Autocorrect defaults to your device’s language settings, which may not match your audience |

The psychological trigger: Hypercorrection drives most errors.

Writers think “ageing” is more proper because it’s longer and less common in global media. This comes from feeling insecure about language. The truth is simpler: both spellings are correct in their regions. Picking the wrong one for your audience doesn’t make your writing better—it shows you didn’t research basic publishing rules.

Using both spellings in one document is worse than picking either one. Your brain’s word recognition system sees the change as an error, even when both forms are technically correct. The mental interruption breaks the reading flow.

Practical Tips and Field Notes

The aging vs ageing choice becomes automatic once you learn the decision rules. Until then, checking your work prevents embarrassing mistakes.

The Editor’s Field Note

In 2019, I was editing a global pharmaceutical company’s annual report—a document that would reach shareholders on five continents. The research division, based in Boston, had written their entire clinical trials section using “aging” to describe geriatric drug studies. The communications team in London had drafted the executive summary using “ageing” throughout.

When I caught the mismatch, I sat in that conference room, red pen hovering, thinking through the implications. The report would be filed with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission—an American legal requirement—but sent mainly to British and European investors. The pharmaceutical division was American. The parent company was British.

Here’s what I learned under that pressure: the legal filing location takes priority. We standardized to “aging” because American regulatory documents require American spelling. We added a note in the UK press release explaining the American spelling reflected SEC requirements. Nobody complained. The lesson? Legal and regulatory context beats audience preference.

Details from that day still stick: the deadline clock on the wall counting down to the filing window, the smell of too many coffees, the weight of 10,000 shareholders depending on getting this right. That’s when I built my mental checklist for regional variants.

Mnemonics and Memory Aids

The Atlantic Test: If your main audience lives on the American side of the Atlantic, write “aging.” If they’re on the British side, write “ageing.” Simple geography.

The ‘E’ for England: British English keeps the ‘e’ in “ageing.” Remember: E for England, E in ageing.

The Webster Shortcut: Americans simplify. Webster simplified. American = aging (shorter). British = ageing (keeps the ‘e’).

Publication Location Logic: Where will this be published? That location’s spelling wins.

These tricks work because they skip the complex grammar and focus on making quick decisions. Your brain doesn’t need to know the full history—it just needs a reliable pattern to follow.

Conclusion

The aging vs ageing split shows that correct spelling depends on geography, not absolute rules.

Choose “aging” for American audiences and publications following U.S. standards. Pick “ageing” for British, Australian, and New Zealand contexts where traditional Commonwealth rules apply. For Canadian readers, “aging” is preferred but “ageing” works in formal settings.

Good writing doesn’t come from choosing one variant as always superior. It comes from consistently using the right regional standard to match your publication and audience. In 2026, digital media favors “aging” globally, but professional publishing still honors regional preferences.

FAQs

Both are correct. “Aging” is standard American English. “Ageing” is standard British English.

Canada primarily uses “aging” following American convention, though “ageing” appears in formal documents with British institutional ties. Canadian style guides recommend “aging.”

Noah Webster’s 1806-1828 spelling reforms eliminated silent letters to simplify American English and distinguish it from British orthography, resulting in “aging” without the ‘e.’

No. American publications, academic journals, and professional documents require “aging.” Using “ageing” signals unfamiliarity with American conventions and will be flagged by editors.

“Aging” dominates globally due to American media influence, but “ageing” remains standard in formal British, Australian, and New Zealand publications.

No. Both spellings are pronounced identically. The difference is purely orthographic (visual spelling), not phonological (sound).

No. Preserve the original author’s spelling in direct quotations. Use square brackets [sic] only if the original contains an actual error, not a regional variant.

Yes. “Anti-aging” (American) and “anti-ageing” (British) are both hyphenated when used as compound adjectives before nouns: “anti-aging cream.”

Match the journal’s publication location. American medical journals use “aging.” British medical journals use “ageing.” Check the journal’s author guidelines.

Only if your language settings match your target audience. Set your word processor to “English (United States)” for “aging” or “English (United Kingdom)” for “ageing.”