Marquee refers to a canopy over an entrance or a large outdoor tent, while marquis designates a European nobleman ranking below a duke and above a count.

These homophones sound identical but occupy separate universes—one architectural and commercial, the other aristocratic and historical. A movie theater displays films on its marquee. A French marquis owned vast estates. The confusion stems from phonological identity paired with complete semantic divergence.

Why Do These Words Trip Up Your Brain?

The confusion is neurological, not careless. Your brain processes homophones through executive control systems in the left middle frontal gyrus.

When you hear /mɑːrˈkiː/, your brain activates both meanings simultaneously. Executive control must select the contextually appropriate word while suppressing the competing alternative. This cognitive operation demands processing resources. Under time pressure or distraction, the selection mechanism fails.

Research demonstrates that homophone processing creates measurable cognitive load. Reaction times slow. Error rates increase. Your brain struggles because marquee and marquis share identical phonological representations but require different orthographic outputs and semantic activations.

Truth is, native speakers make this error regularly in speech-to-text software and rushed writing. The mistake isn’t ignorance—it’s cognitive interference.

Core Concepts and Historical Evolution

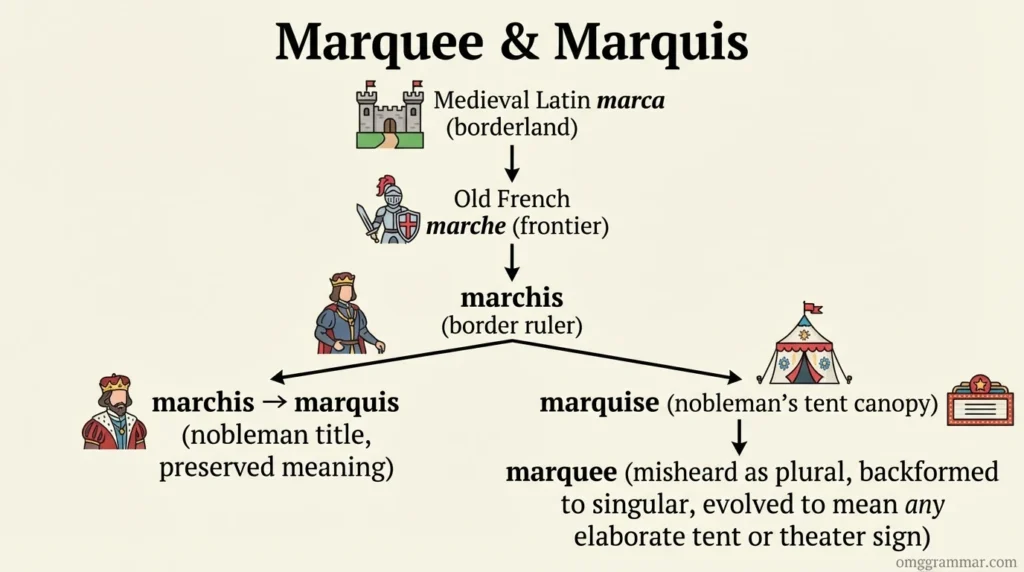

Both words descended from Old French marchis, meaning “ruler of a border territory.” Medieval French derived this from marche (frontier), which itself came from Medieval Latin marca (borderland). The words began as one concept and split through separate evolutionary paths over seven centuries.

Etymology and Old French Border Terminology

The story begins with the Frankish marca, a Germanic loan into Latin meaning “boundary” or “borderland.” Romans used it to describe frontier provinces requiring military governance. By 800 CE, Charlemagne’s empire designated border territories as marches, ruled by marchis—literally “border counts.”

Old French adopted marchis around 1200 CE. A marchis governed unstable frontiers, defending against hostile neighbors. The title ranked above regular counts because border defense carried higher stakes. The word entered Middle English as markis around 1300, eventually standardizing to marquis.

The split occurred during the 1680s. French military nobility distinguished their campaign tents with decorative canopies. These ornate coverings became known as marquises (feminine form of marquis), suggesting “tent suitable for a marquis.” English speakers heard the French plural marquises and misinterpreted it as singular, creating the backformation marquee.

By 1812, marquee meant any elaborate tent. By 1900, American theaters adopted the term for the illuminated canopy projecting over their entrances—the architectural element announcing shows and attracting crowds.

Grammatical Mechanics and Homophonic Orthographic Divergence

Marquee and marquis exemplify pure homophony: identical phonological form, divergent orthography, zero semantic connection. The pronunciation /mɑːrˈkiː/ (or British /ˈmɑːrkwɪs/ for marquis) maps to two separate lexical entries in mental representation.

Homophonic orthographic divergence creates disambiguation challenges absent in synonyms or polysemes. With synonyms, different sounds signal different words. With polysemes, one spelling carries multiple related meanings. Homophones force the brain to rely exclusively on context.

For marquee, check for architectural or entertainment contexts. For marquis, check for nobility, historical references, or European aristocracy. Sound alone cannot guide you—only semantic environment determines correctness.

How Context Determines Meaning: Practical Examples

The words function in mutually exclusive domains. Marquee appears in commercial, entertainment, and event contexts. Marquis appears in historical, biographical, and cultural contexts. Mixing them creates jarring semantic violations.

Formal and Professional Usage

Journalism uses marquee as an adjective meaning “headlining” or “premier.” A marquee player draws crowds. A marquee event generates publicity. This metaphorical extension derives from the theater marquee that advertises the main attraction.

Marquis appears in historical writing and biography. “The Marquis de Lafayette aided the American Revolution.” Historical novels reference titled nobility. Genealogical records document marquis families. The word carries formality and period specificity.

Notice the register difference. Marquee sounds modern and commercial. Marquis sounds classical and aristocratic. Writers attuned to register choose the word matching their document’s tone and subject matter.

Conversational and Informal Contexts

Wedding planners discuss marquee rentals—the large tents sheltering outdoor receptions. British English uses marquee almost exclusively for these event structures, rarely for theater signs.

Americans use marquee for both meanings: the theater sign and metaphorical prominence. “She’s a marquee name in tech” means she’s high-profile, like a name displayed in lights. This usage feels contemporary and media-influenced.

Marquis rarely appears in casual speech unless discussing history or reading historical fiction. “The Marquis of Queensberry Rules” governs boxing—a phrase preserved because the historical figure codified the sport’s regulations in 1867.

The Error Pattern: Why People Mix Them

Spell-check catches marquee/marquis errors only when the word creates grammatical nonsense. “The marquis displayed the show times” might pass automated review because marquis is a valid English word. The sentence makes sense until you realize marquees display information, not noblemen.

The reverse error—”Hire a marquis for the outdoor wedding”—sounds absurd to native speakers but trips up language learners who’ve memorized marquis as “the fancier-looking spelling.” They associate the -is ending with French elegance and deploy it incorrectly.

Literary and Cultural References: How Writers Use These Words

Classic literature and modern journalism employ these homophones in their appropriate contexts, revealing how semantic boundaries function in practice.

Historical Usage in Classic Texts

Oscar Wilde wrote in The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890): “The Marquis of Stirling bowed to Lady Narborough and looked at Dorian Gray.” Wilde uses marquis correctly for British nobility, demonstrating how the title appeared in upper-class Victorian society.

Henry James’s The American (1877) features “the Marquis de Bellegarde,” a French nobleman. James distinguishes between English marquess (British spelling) and French marquis, showing awareness of regional spelling conventions.

Notice neither author would write “the marquee” when referencing nobility. The semantic boundary was clear even when both words were relatively new to English. Writers respected the domain-specific nature of each term—marquis for aristocracy, marquee for structures.

Modern Application Across Media

Contemporary journalists write about marquee matchups in sports—games featuring star athletes that drive ticket sales. Entertainment coverage references marquee films—blockbusters receiving prime theater placement and advertising.

Historical documentaries discuss the Marquis de Sade or the Marquis de Montrose, maintaining the nobility title’s original spelling and meaning. Biography maintains historical accuracy by preserving period-appropriate terminology.

Tech journalism uses marquee to describe prominent product launches or industry-leading figures. “Apple’s marquee event” means their flagship announcement. This metaphorical usage extends from the theater marquee’s function as the primary attention-grabber.

Synonyms, Variations, and Linguistic Neighbors

Understanding related terms clarifies when marquee and marquis fit best within broader semantic fields.

Semantic Neighbors and Their Distinctions

For marquee (structure), synonyms include: canopy, awning, tent, pavilion. Canopy emphasizes overhead protection. Awning suggests a smaller, building-attached structure. Tent indicates portability. Pavilion implies elegance and event formality.

For marquee (sign), alternatives include: signage, billboard, display. These lack marquee’s specific association with entertainment venues and illuminated lettering.

For marquis (nobility), the British equivalent is marquess—same rank, different spelling. Earl and count rank below. Duke ranks above. These titles form a hierarchy of hereditary peerage with specific parliamentary and social privileges.

The French feminine form is marquise, meaning a marquis’s wife or a woman holding the rank in her own right. This spelling also applies to a diamond cut and a ring style—metaphorical extensions from nobility to luxury goods.

Visualizing the Etymology Split

Etymology diagram illustrating how marquee and marquis both derive from Old French marchis but diverged through separate semantic evolution paths—one preserving nobility meaning, the other shifting through military tent decoration to modern commercial signage.

Regional Spelling Variations

American and French usage prefer marquis for the nobleman. British usage prefers marquess (pronounced /ˈmɑːrkwɪs/), reflecting English spelling conventions. Both refer to identical rank in aristocratic hierarchy.

Marquee shows no regional variation—all English-speaking countries use this spelling for tents and theater signs. The word entered English through misinterpretation rather than through formal borrowing, creating a uniform spelling across dialects.

Common Mistakes: Where Writers Go Wrong

The homophone trap catches both native speakers and learners. Errors follow predictable patterns driven by phonological identity and semantic unfamiliarity.

| Incorrect | Correct | The Fix |

| The marquis at the Roxy Theater showed Casablanca | The marquee at the Roxy Theater showed Casablanca | Theaters display information on marquees (signs), not noblemen. Context requires the architectural term. |

| We rented a marquis for the outdoor reception | We rented a marquee for the outdoor reception | Event tents are marquees. Marquis is a person, not a structure you rent. |

| The Marquee de Lafayette fought in the Revolution | The Marquis de Lafayette fought in the Revolution | Historical titles require marquis (nobleman), not marquee (tent/sign). |

| The marquis player scored three goals | The marquee player scored three goals | Sports journalism uses marquee as an adjective meaning “star” or “headlining.” |

| The wedding marquee was held at the estate | The wedding marquee was held at the estate | You hold an event “under” a marquee or “in” a marquee. The marquee is the tent, not the event. Say “The wedding was held under a marquee” or “A marquee was erected for the wedding.” |

Psychological Trigger: Orthographic hypercorrection drives errors. English learners see -is as “more French” and “more sophisticated” than -ee. They overgeneralize this pattern, using marquis everywhere. The brain prioritizes morphological patterns (foreign-looking endings signal formality) over semantic appropriateness.

Additionally, the recency effect influences selection. If you recently read about nobility, marquis becomes primed. Your brain defaults to the more recently activated representation, even when context demands marquee.

Practical Tips and Field Notes

Mastery requires context sensitivity and etymological awareness. A few strategic checkpoints prevent most errors.

The Editor’s Field Note

In 2017, while editing a historical romance manuscript, I found 73 instances of “marquee” where “marquis” belonged. The author had written elaborate scenes at country estates, describing “the marquee’s vast holdings” and “the marquee’s political influence.”

I remember the phone call. Manuscript red-lined. Coffee lukewarm. “Your marquees are noblemen,” I said. “They own lands, attend Parliament, and marry heiresses. Marquees are tents and theater signs. Your hero needs to be a marquis.”

Silence. Then: “But marquee looks more elegant.”

That sentence revealed the error’s source—aesthetic preference trumping semantic accuracy. The author selected spelling based on visual appeal, not meaning. Under deadline pressure to finish the 400-page manuscript, she’d defaulted to the “prettier” option and applied it uniformly.

We spent two hours doing a global search-and-replace, checking every instance for context. The delay cost a week’s publication timeline. The lesson was expensive: homophone errors demand contextual verification. Spell-check won’t save you. Only semantic awareness prevents these mistakes.

Mnemonics and Memory Aids

Use the “EE for Entertainment, IS for Nobility” rule. Marquee contains “ee” like “screen” and “scene”—entertainment contexts. Marquis ends in “is” like “aristocratic” contains “is.”

Try the Physical Test: Can you touch it or rent it? Use marquee. Is it a person with a title? Use marquis.

When in doubt, check for dates. If the sentence involves years before 1950, suspect marquis (nobleman). If discussing modern events, advertising, or structures, suspect marquee.

Conclusion

The marquee vs marquis confusion stems from a seven-century linguistic split that began with a single Old French word meaning “border ruler.” One path preserved the nobility meaning. The other twisted through military decoration, tent design, and theater architecture to describe physical structures and metaphorical prominence.

Your brain struggles because executive control must select between phonologically identical representations. Context provides the only disambiguation mechanism. Marquee appears in architectural, commercial, and entertainment domains. Marquis appears in historical, biographical, and aristocratic contexts.

Master the domain distinction. Train your eye to catch the orthographic difference (-ee vs -is). Verify context before committing to spelling. Automated tools won’t flag marquee used incorrectly if the sentence remains grammatically coherent.

The error isn’t ignorance—it’s cognitive interference. Awareness of the neural processing challenge transforms confusion into competence. Use this knowledge to write with precision.

FAQs

Marquee is a tent or theater sign; marquis is a nobleman. Marquee refers to the canopy over theater entrances or large event tents. Marquis designates European aristocratic rank below duke and above count.

No, they cannot be interchanged. Using marquee for a nobleman or marquis for a tent creates semantic nonsense.

Both are pronounced /mɑːrˈkiː/ in American English. British speakers may say /ˈmɑːrkwɪs/ for marquis. The identical sound explains the confusion.

Yes, they refer to the same rank. Marquess is British spelling; marquis is French/American spelling. Both designate a nobleman ranking below duke.

Use “marquee” as an adjective meaning “headlining” or “premier” in sports and entertainment contexts. A marquee player is a star athlete.

The feminine is marquise in French, or marchioness in British English.

Homophone confusion causes the error. The brain hears identical sounds but must select between two different meanings based solely on context.

No, you rent a marquee (tent). A marquis is a person with a title, not a rentable structure.