A chip off the old block describes someone who closely resembles a parent in appearance, behavior, or character. The phrase originated from 17th-century stonecutting and woodworking, where a small piece chipped from a larger block retained the same properties as its source. Today, this idiom remains one of English’s most enduring expressions for capturing generational similarities.

Why Does Your Brain Stumble Over This Phrase?

Your cognitive system processes idioms differently than regular sentences. When you encounter a chip off the old block, your brain activates what linguists call the Dual-Route Processing Model.

Here’s what happens in those milliseconds: Your language centers attempt to decode the literal meaning first. Chips. Blocks. Wood. None of this connects to human relationships. Meanwhile, your semantic memory searches for stored figurative meanings. This creates what neuroscientists call cognitive load—the mental effort required to suppress the irrelevant literal interpretation while retrieving the correct idiomatic one.

Truth is, non-native speakers often struggle here. They visualize actual woodworking instead of family traits. Even native speakers occasionally pause when they hear this phrase used in unexpected contexts, like describing corporate mentorship or artistic influence. That hesitation? That’s your Dual-Route Processing Model working overtime.

Core Concepts and Historical Evolution

The journey from carpenter’s workshop to everyday conversation spans nearly 2,400 years. Ancient Greeks first captured this concept when poet Theocritus wrote about resemblance in his Idylls around 270 BCE. He referenced a chip being similar to its source material—a metaphor that craftsmen of his era understood instantly.

Fast-forward to 1621. Bishop Robert Sanderson penned the earliest English version in his Sermons: “Am not I a child of the same Adam… a chip of the same block, with him?” Notice the wording—same block, not old block. This matters because it originally emphasized shared origins rather than generational succession.

Etymology and Metaphorical Crystallization

The Proto-Germanic root kipp meant “to cut off” or “to chip away.” Old English speakers used cipp for small wood fragments. Meanwhile, blokk entered English through Old French bloc, ultimately from Middle Dutch.

But here’s where Metaphorical Crystallization gets interesting. During the 1600s, England’s printing revolution standardized language in unprecedented ways. Craftsmen’s metaphors—previously fluid oral expressions—became fixed written phrases. The idiom froze at this moment in linguistic history.

John Milton wrote in 1642: “How well dost thou now appeare to be a Chip of the old block.” He still capitalized Chip and old block as concrete nouns. By 1700, lowercase letters signaled the phrase had completed its transformation from literal description to abstract idiom. The metaphor had crystallized.

Grammatical Mechanics and Frozen Nominal Phrase Structure

This idiom functions as what grammarians call a Frozen Nominal Phrase. You cannot alter its structure without destroying meaning. Watch what happens:

The Golden Rule: You cannot pluralize, possessivize, or modify the internal components of a chip off the old block without rendering it meaningless or awkward.

Try saying “a chip off the older block” or “chips off the old blocks.” Your ear immediately rebels. This syntactic rigidity distinguishes true idioms from regular metaphors. Regular metaphors bend. Idioms break.

Linguists classify this as a determiner-noun-prepositional phrase construction where the indefinite article “a” can become “the” in specific contexts (“He’s the chip off the old block in that family”), but internal modification remains impossible. This is phraseological freezing in action.

Contextual Examples

Understanding how a chip off the old block functions across different registers reveals its flexibility. Each context requires subtle adjustments in tone and emphasis while maintaining the core meaning.

Formal Academic Writing

Academic prose typically avoids idioms, but this one occasionally appears in sociology and psychology journals when discussing hereditary traits. Scholars employ it to signal accessible writing without sacrificing precision.

A formal example: “The longitudinal study revealed behavioral patterns suggesting the younger subject was indeed a chip off the old block, exhibiting risk-assessment tendencies statistically identical to the parental figure.” Notice how the idiom softens dense academic language. The active voice construction (subject exhibited) maintains professional tone while the idiom provides relatable imagery.

Casual Conversation

Conversational usage permits—even expects—contractions and looser syntax. You’ll hear it in parent-teacher conferences, family gatherings, and workplace small talk.

Text message example: “Did you see Jake’s science fair project? Total chip off the old block. His dad was doing robotics at that age too”

The response: “Right?? Give it 10 years and he’ll be teaching at MIT lol”

Tone shifts dramatically here. The idiom becomes shorthand for family pride mixed with humor. No need for lengthy explanation—everyone knows exactly what you mean.

The Nuance Trap

Here’s where native intuition separates from technically correct usage. Consider these two sentences:

Correct but awkward: “She is resembling a chip off the old block in her mathematical abilities.”

Native-sounding: “She’s a chip off the old block when it comes to math.”

Both are grammatically defensible. But the first commits what linguists call register violation—mixing progressive aspect with a frozen idiom. Native speakers instinctively avoid this. The second flows naturally because it respects the idiom’s internal grammar while adding appropriate context.

How Writers Have Used This Phrase Through History

Literary references to a chip off the old block reveal how the expression evolved from explicit family descriptions to broader cultural commentary. Tracking its usage illuminates changing attitudes toward heredity, social class, and individual identity.

Classic Literature

Areopagitica — John Milton — 1644

Milton didn’t reference family resemblance directly but used the stonecutting metaphor throughout his work, establishing the intellectual foundation for the idiom’s figurative leap. His contemporary audiences, steeped in craft guild culture, immediately grasped comparisons between material properties and human qualities.

Reflections on the Revolution in France — Edmund Burke — 1790

Burke employed variations of this phrase when discussing political inheritance: those born to leadership supposedly carried innate qualities from their lineage. His usage reflected Enlightenment-era debates about nature versus nurture. Burke argued that political stability required leaders who were, effectively, chips off aristocratic blocks.

This conservative perspective framed the idiom as validation for inherited power. Writers responding to Burke—Thomas Paine among them—challenged this interpretation, arguing that character should be judged independently. The idiom thus became contested ground in 18th-century political discourse.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer — Mark Twain — 1876

Twain used familial resemblance as comedic device throughout his novels, though he favored “cut from the same cloth” over “chip off the old block.” His avoidance is telling. By the 1870s, the phrase had become so common in American journalism that literary authors sought fresher alternatives.

Modern Stylistic Simulation

Contemporary thriller writers deploy this idiom strategically. In stories featuring dynastic crime families or inherited trauma, describing a character as a chip off the old block immediately establishes generational patterns without requiring lengthy exposition.

Consider how modern psychological suspense might use it: The detective examines photographs spanning four generations. Same cold eyes. Same cruel smile. “A chip off the old block,” she mutters, understanding that the violence didn’t start with this suspect. It never does in families like this.

Corporate dramas use the phrase differently. When a young executive exhibits the same ruthless negotiation tactics her mentor perfected decades earlier, colleagues whisper that she’s a chip off the old block. Here the idiom extends beyond blood relations to professional lineage—a 21st-century adaptation of a 17th-century metaphor.

Synonyms and Variations

Language provides multiple ways to express familial resemblance, each with distinct connotations. Comparing these alternatives reveals how a chip off the old block occupies its unique semantic space.

Semantic Neighbors

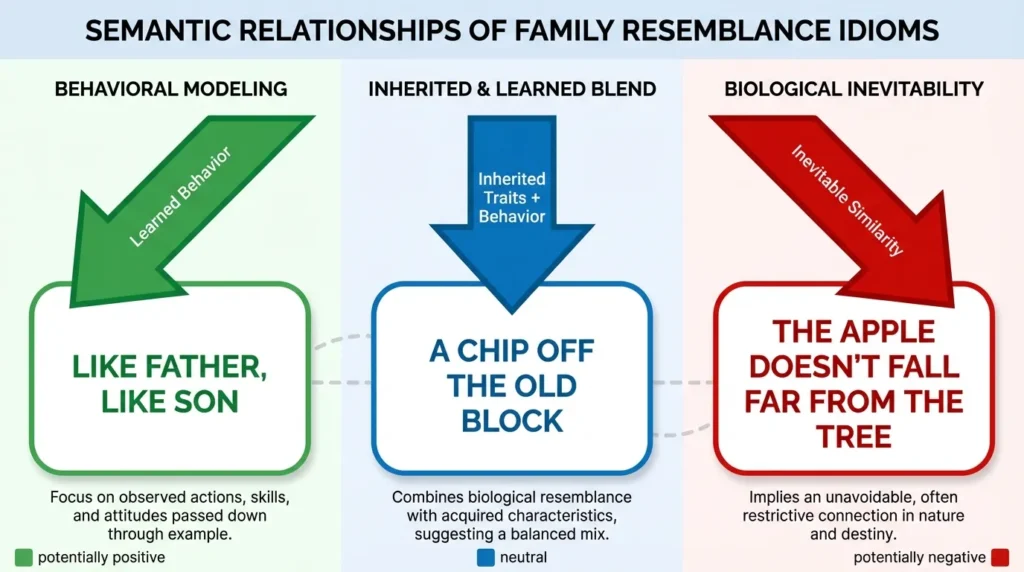

Like father, like son (or like mother, like daughter): This phrase emphasizes direct causation. The implication is that children model behavior after observing parents. It carries slightly stronger judgment—often suggesting fault as much as credit.

The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree: This rural metaphor emphasizes inevitability. Gravity ensures apples land near their source. The phrase suggests you cannot escape your origins, sometimes with negative undertones.

Cut from the same cloth: Originally a tailoring metaphor, this phrase describes identical character without hierarchical parent-child implications. You’ll hear it for siblings or peers who share traits despite different backgrounds.

Spitting image: This exclusively visual idiom describes physical resemblance so precise that one person could be the “spit” (exact replica) of another. It lacks the behavioral component that a chip off the old block carries.

The key distinction? A chip off the old block uniquely combines physical, behavioral, and dispositional resemblance while maintaining neutral valence. It can be complimentary, critical, or purely observational depending on context.

Visualizing the Difference

Semantic relationship diagram comparing three family resemblance idioms, showing how “a chip off the old block” occupies the neutral center position combining both inherited and learned characteristics, while alternative phrases emphasize either behavioral modeling or biological inevitability.

Regional Variations

American and British English use this idiom identically—a rarity among idioms. However, frequency differs by region. British speakers favor “chip off the old block” in formal contexts, while Americans use it across all registers.

Australian English sometimes playfully modifies it to “chip off the old chopping block,” referencing bushcraft traditions. New Zealand speakers occasionally say “chip off the old kauri,” referencing native kauri trees. These regional variants remain rare but demonstrate how idioms adapt to local culture while maintaining core meaning.

Common Mistakes When Using This Phrase

| Incorrect | Correct | The Fix |

| “He’s a chip of the old block” | “He’s a chip off the old block” | Preposition matters: “of” suggests belonging, but “off” correctly implies separation while maintaining connection. |

| “They’re chips off the old blocks” | “They’re chips off the old block” (or each is “a chip”) | Block remains singular even when describing multiple children, as they all originate from the same metaphorical source. |

| “She’s quite a chip off her mother’s old block” | “She’s a chip off the old block—just like her mother” | Never insert possessives into the frozen phrase structure. Add clarifying context after the idiom instead. |

| “He was being a chip off the old block” | “He was acting like a chip off the old block” | The idiom functions as a noun phrase describing identity, not a verb phrase describing action. |

| “She’s a fresh chip off the old block” | “She’s a chip off the old block” | Resist the temptation to modify with adjectives. The phrase works precisely because of its semantic compression. |

These errors stem from what psycholinguists call hypercorrection—the tendency to apply grammar rules to idioms that resist standard grammatical analysis. Your brain recognizes “block” as a noun that should be pluralizable. But Frozen Nominal Phrases override normal grammar rules.

Speakers also overgeneralize based on similar phrases. Because you can say “a different kettle of fish,” your brain suggests “a younger chip off the older block” should work. It doesn’t. Each idiom operates under its own internal logic.

Practical Tips and Field Notes

Real-world idiom usage requires more than definition memorization. You need contextual awareness and timing. These strategies come from three decades of editing work where precision with figurative language determined whether documents succeeded or failed.

The Editor’s Field Note

In 2019, while editing a legal brief for a custody case, I encountered this exact phrase used improperly. The attorney had written: “The minor child demonstrates behaviors suggesting he is a chip off the old block, inheriting his father’s documented aggressive tendencies.”

The phrase crashed in this context. Why? Legal documents require neutral, evidence-based language. “Chip off the old block” carries affectionate or at minimum neutral connotations. Using it to describe inherited violence felt jarring—almost flippant.

I spent three hours on a Friday evening rewriting that section. The client deadline loomed. My red pen transformed the sentence to: “The minor child exhibits behavioral patterns consistent with documented paternal aggression.” Dry. Precise. Legally defensible.

The lesson stuck with me. Idioms fail when register mismatches context. That attorney wasn’t wrong about meaning—just about appropriateness. In the margin of my notes from that night, I wrote: “Idioms are like salt. Essential in correct doses. Ruinous when overdone or misplaced.”

Two weeks later, the opposing counsel cited our brief’s clarity as a reason for settling rather than proceeding to trial. Words matter. The difference between good writing and great writing often comes down to knowing when to use idioms and when to discard them.

Mnemonics and Memory Aids

Need to remember when this idiom works? Try this device:

CHIP helps you remember: Character, Heritage, Identity, Parent.

If your sentence addresses all four elements—someone’s character resembling their heritage through identity tied to a parent—then a chip off the old block fits perfectly.

Another trick: If you can replace the phrase with “takes after their mom/dad” without losing meaning, you’re using it correctly.

Conclusion

Understanding a chip off the old block means more than memorizing a definition. This phrase embodies how language captures complex human relationships through simple metaphors.

The idiom’s power lies in its specificity. It doesn’t just say “similar.” It evokes the exact moment when a stone chips from its source—that instant when something new emerges while remaining fundamentally unchanged. You carry your origins forward. You’re simultaneously separate and identical.

Use this phrase when you want to acknowledge continuity across generations. Recognize that language evolved this expression because humans needed words for describing the mysterious ways children echo their parents. Whether through genetics, environment, or some combination, we see ourselves reflected in those who come after us.

The next time you hear someone described as a chip off the old block, you’ll understand the 2,400-year journey that phrase traveled to reach your ears. From ancient Greek poetry through medieval workshops to your modern conversation—that’s the staying power of well-crafted metaphor.

FAQs

It means a person closely resembles their parent in appearance, behavior, or personality. The phrase comes from woodworking, where a chip broken from a block retains the same characteristics as the original material.

Yes, absolutely. While historically used for fathers and sons, modern usage applies to any parent-child relationship regardless of gender. You’ll hear “she’s a chip off the old block” frequently in contemporary speech.

No, it’s neutral. Context determines whether the resemblance is complimentary, critical, or simply observational. If someone inherits admirable traits, it’s praise. If they inherit problematic behaviors, it carries warning.

The earliest English version appeared in 1621 in Bishop Robert Sanderson’s Sermons. However, the concept dates to ancient Greek literature around 270 BCE. The modern wording “chip off the old block” became standard by the late 1800s.

Technically yes, but most native speakers say “they’re each a chip off the old block” or keep block singular. The phrase resists pluralization because it functions as a fixed expression rather than regular grammar.

“Chip off the old block” emphasizes inherent resemblance, while “like father, like son” suggests learned behavior. The first is more neutral; the second often implies causation or modeling.

Yes, many languages have equivalent expressions. Spanish uses “de tal palo, tal astilla” (from such stick, such splinter), while German says “der Apfel fällt nicht weit vom Stamm” (the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree). The metaphor of resembling one’s source is universal.

Yes, increasingly so. Modern usage extends to mentors and proteges, particularly in professional contexts.