Is summer capitalized? No, “summer” is a common noun and remains lowercase in standard writing. You capitalize it only when it starts a sentence, appears in a title, or functions as part of a proper noun like “Summer Olympics.”

Why Does Your Brain Want to Capitalize Summer?

Your brain stumbles over season names because of pattern interference. When you write “Summer 2024” or see “Summer Collection” in advertisements, your visual memory stores these capitalized versions. This creates a false pattern that triggers overgeneralization—a cognitive phenomenon where your brain applies a rule too broadly based on limited exposure.

The confusion deepens when you compare seasons to months. You write “July” with a capital J, so why not “summer” with a capital S? Your working memory tries to create consistency where none exists. Months are proper nouns; seasons are not.

Truth is, this mistake appears in professional writing more often than you’d think. The distinction isn’t arbitrary—it reflects a fundamental grammatical category that separates generic time periods from named ones.

What Makes Season Capitalization Different?

Seasons follow the same capitalization rules as other common nouns describing general concepts or time periods. “Summer” sits in the same grammatical category as “morning,” “afternoon,” or “week”—all lowercase unless grammar demands otherwise. This pattern emerged from Middle English scribal practices, where capitalization served primarily to mark sentence boundaries and proper names rather than to emphasize important words.

The Historical Shift in English Capitalization

English capitalization evolved dramatically between 1500 and 1800. Early Modern English writers capitalized most nouns, following conventions borrowed from German printing houses. You can see this in the Declaration of Independence, where words like “Life,” “Liberty,” and “Happiness” receive capital letters not because they’re proper nouns, but because 18th-century convention treated important concepts as worthy of visual distinction.

The reform came gradually. By the mid-1800s, grammarians pushed for standardization, arguing that excessive capitalization slowed reading comprehension. They established a binary system: proper nouns (specific names) get capitals, while common nouns (generic categories) stay lowercase. Seasons fell into the common noun category because they describe recurring natural periods, not unique entities.

Common Nouns vs. Proper Nouns in Modern Usage

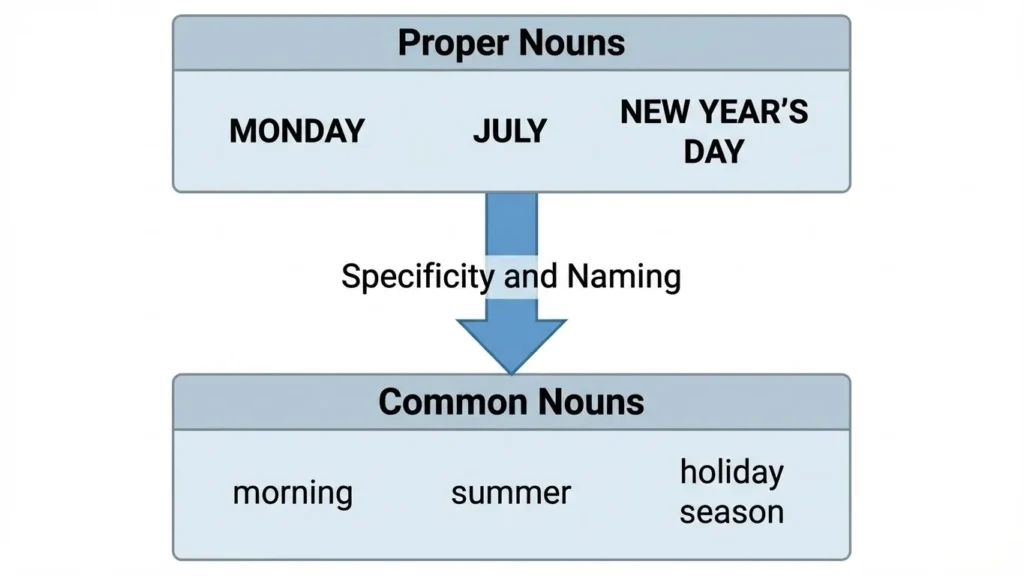

The grammatical distinction hinges on specificity and naming. A proper noun labels a unique entity—Mount Everest, Tuesday, Amazon River. A common noun describes a category or general concept—mountain, weekday, river.

When “summer” refers to the general season, it functions as a common noun and stays lowercase.

Seasons name recurring natural phenomena that happen everywhere on Earth. You can’t own summer or visit it at a specific address. Compare this to months, which function as proper nouns because they name specific divisions of the calendar—named entities with fixed positions. July always occupies the same slot; summer shifts based on hemisphere and climate.

The test is simple: if you can say “a” or “the” before the word and it still describes something generic, it’s common. You write “a summer afternoon” or “the summer of 2024,” where summer describes a type of time period rather than naming it.

How Is Summer Capitalized in Different Contexts?

The word “summer” takes a capital letter in three specific scenarios, while remaining lowercase in general use. These exceptions follow standard English capitalization rules rather than creating special cases for seasons.

Formal Academic Writing

Lowercase prevails in scholarly work. You write “The data was collected during summer 2023” in a research paper. The season serves as a temporal marker, nothing more.

Academic style guides—APA, MLA, Chicago—align on this point. They treat seasons as common nouns describing when events occurred. The citation reads “Smith, J. (2023, summer)” with lowercase because you’re specifying a time period within the year, not naming a formal division.

Scientific papers handle it identically: “Summer precipitation patterns shifted” uses lowercase because the season describes a climatological period. However, if a study creates a specific program name, you capitalize: “The Summer Research Initiative began in 2020.”

Conversational Digital Communication

Text messages and emails follow the same rule, though you’ll see variations. “cant wait for summer!” breaks capitalization rules for stylistic reasons—the lowercase creates a casual tone. But standard writing maintains lowercase: “I’m planning a summer trip to Greece.”

Social media amplifies confusion. Hashtags like #SummerVibes capitalize for visibility and tradition rather than grammar. Posts declaring “SUMMER IS HERE” use all-caps for emphasis, not because grammar requires it. When you return to normal prose, the season drops back to lowercase.

Tone shifts don’t change the rule. Whether you’re texting a friend or drafting an email to your boss, “summer” stays lowercase unless it opens a sentence: “Summer brings tourists to the coast.”

The Proper Noun Exception

Capitalization appears when summer joins a proper noun or forms part of an official name. “Summer Olympics” capitalizes both words because the phrase names a specific event occurring every four years. You’re not discussing summer generally—you’re identifying the Games.

Course titles and programs work the same way: “I enrolled in Summer Session II” capitalizes because it names a specific academic term at your institution. Compare this to “I’m taking classes this summer,” where the season remains generic. Event names like “Summer Solstice Festival” or “Summer Concert Series” get capitals because they’re official titles.

Brand names and marketing campaigns capitalize liberally—”Summer Sale 2024″—but this reflects commercial styling rather than grammatical necessity. The rule bends for visual impact in advertising, but standard prose keeps it lowercase.

How Have Writers Handled Summer Capitalization?

Literary examples reveal consistent lowercase usage across centuries, though context determines exceptions. Writers treat summer as a common noun describing atmosphere, time, or season rather than as a named entity.

Classic Texts and Seasonal References

Shakespeare wrote “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” in Sonnet 18, keeping summer lowercase throughout the poem. The possessive form “summer’s” appears six times in his complete works, never capitalized mid-sentence. He treats the season as a quality—warmth, beauty, transience—not as a proper noun.

Thoreau’s “Walden” offers direct evidence: “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.” His later passage states: “A lake is the landscape’s most beautiful and expressive feature. It is earth’s eye; looking into which the beholder measures the depth of his own nature.” When discussing seasons, he writes “in summer” and “during winter” with consistent lowercase.

Contemporary Style in Modern Publishing

Modern publishing houses enforce lowercase for seasons in fiction and nonfiction alike. Thriller writers set scenes “during a hot summer in Texas” to establish atmosphere. The season creates mood and timing without requiring capitalization.

Memoirs anchor events to seasons temporally: “That summer changed everything” uses lowercase because the author references a personal time period rather than naming an event. However, if that summer became a titled chapter—”The Summer of ’69″—capitals appear because you’ve created a proper noun through naming.

Business writing maintains the standard. Annual reports state “Summer sales exceeded projections” with lowercase, treating the season as a fiscal quarter descriptor. Marketing materials bend rules—”Summer Savings Event”—but formal correspondence stays grammatically correct.

What Other Time Words Follow Similar Rules?

Season names share capitalization patterns with other temporal descriptors, creating a consistent system across English grammar. Understanding these parallel cases clarifies why summer stays lowercase.

Comparing Seasons to Months and Days

Months and days function as proper nouns because they name specific, named positions in the calendar. “July” identifies the seventh month, a fixed entity with a unique identity. You can’t move July or create another July—it occupies one designated slot.

Days work identically. “Tuesday” names the third day of the week, a specific position that recurs but maintains its identity. The pattern repeats: Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday—seven named entities, all capitalized.

Seasons operate differently. Summer describes a climatological period that shifts based on hemisphere and varies in length depending on how you measure it. The astronomical summer (solstice to equinox) differs from meteorological summer (June through August). This flexibility and lack of fixed boundaries keeps seasons in the common noun category.

Other temporal common nouns include: morning, afternoon, evening, night, dawn, dusk, twilight. All lowercase. All describing periods rather than naming them. When you write “Monday morning,” the day gets capitalized, the time period doesn’t.

Regional Style Differences

American and British English align on season capitalization—both keep them lowercase. This represents one of the rare points of total agreement between style guides across the Atlantic.

Canadian English follows British conventions here, maintaining lowercase for all four seasons. Australian style guides concur. The consistency exists because season capitalization rules predate the divergence of English dialects across former British territories.

Some languages capitalize differently. German capitalizes all nouns, including “Sommer.” French keeps “été” lowercase, matching English. Spanish uses “verano” in lowercase. The variation reflects broader grammatical patterns rather than specific season treatment.

What Mistakes Do People Make with Season Capitalization?

Writers commonly overcapitalize seasons due to visual exposure to marketing materials and confusion with calendar months. These errors appear across professional and casual writing, creating inconsistency that weakens credibility.

| Incorrect | Correct | The Fix |

| I love Summer weather | I love summer weather | Seasons are common nouns; keep lowercase |

| The Fall semester begins soon | The fall semester begins soon | Only capitalize if part of official title: “Fall 2024 Semester” |

| We’re planning a Winter vacation | We’re planning a winter vacation | Lowercase unless it’s “Winter Olympics” or similar proper noun |

| Spring is my favorite Season | Spring is my favorite season | Neither word needs capitals mid-sentence |

| The Summer of 2024 was hot | The summer of 2024 was hot | Don’t capitalize season even when specifying year |

The psychological trigger is hypercorrection—you’ve internalized that time words need capitals because months and days do. Your brain extends this pattern to seasons without recognizing the categorical difference. This mental shortcut creates errors that persist even after you learn the rule.

Another factor: authority bias. When you see “Summer Sale” in professional marketing materials, your brain assumes the capitalization must be correct. You absorb the pattern and reproduce it, not realizing that commercial styling deliberately breaks grammatical rules for visual impact.

When Should You Capitalize Summer in Practice?

Real-world application requires recognizing context and function. The season stays lowercase in most writing, with capitals appearing only in specific structural positions or proper nouns.

Editing Professional Documents

I once edited a university press manuscript where the author had capitalized all four seasons throughout 300 pages. The text read: “During the Summer of 1945, researchers gathered data across three continents. By Fall, they had compiled results showing…” Red ink covered every page.

The author insisted the capitalization added “weight” to seasonal transitions. We spent two hours on a call where I explained that readers don’t assign importance based on capital letters—they assign it based on content and structure. The arbitrary capitals actually distracted from the argument, forcing readers to pause and question the choice.

Deadline pressure made it worse. We had three days to finalize proofs, and global find-replace wouldn’t catch phrases like “Summer Olympics” where capitals were correct. I ended up reading the entire manuscript again, evaluating each instance individually. The author learned the rule, but it cost us both time and tested my patience.

That experience taught me to address capitalization errors early. Now, when I see seasonal capitals in a first draft, I explain the rule immediately. Prevention beats correction.

Memory Tricks for Season Capitalization

Remember the phrase: “Seasons change, but names stay the same.” Months and days have names—July, Tuesday. Seasons describe changes in nature—summer, winter. Names get capitals; descriptions don’t.

Another trick: Can you say “a” before it? If yes, it’s common. You write “a summer day” or “a winter storm,” proving these words describe types rather than name entities. You can’t write “a July” or “a Tuesday” and have it make grammatical sense.

Think of seasons as adjectives in disguise. When you write “summer heat,” summer modifies heat just like “intense heat” would. Adjectives don’t get capitals mid-sentence. Neither do seasons in this function.

Conclusion

Keep seasons lowercase unless they start a sentence or form part of a proper noun. This pattern aligns with broader capitalization logic, treating seasons like other common nouns that describe rather than name. When you internalize this distinction, you’ll apply it automatically across all temporal words, creating consistency that marks you as a skilled writer.

FAQs

No, summer stays lowercase in standard sentence usage. You only capitalize summer when it starts a sentence, appears in a title, or forms part of a proper noun like Summer Games.

No. Summer vacation uses summer as a descriptive adjective modifying the common noun vacation. Both words stay lowercase unless starting a sentence: “Summer vacation begins in June.”

It depends on context. Academic institutions capitalize “Summer 2026” as an official term label on transcripts and schedules. In regular prose describing events during that time period, write “summer 2026” in lowercase.

No. Academic papers, business reports, and professional documents keep summer lowercase. The formality of your writing doesn’t change capitalization rules for common nouns.

Yes, when following title case conventions. In a book title like “The Summer of Discovery,” summer gets capitalized because title case capitalizes major words. In sentence case (“The summer of discovery”), it stays lowercase.

No. Both varieties keep summer lowercase in standard usage and capitalize it only in proper nouns, at sentence starts, or in titles.

Months name specific positions on the calendar—June always refers to the same month globally. Summer describes a climate period that varies by hemisphere and doesn’t name a specific entity.