Alright vs All Right: The difference between “alright” and “all right” boils down to formality and acceptance. “All right” remains the only universally accepted spelling in formal writing, while “alright” has gained traction in casual contexts despite ongoing resistance from traditional style guides.

Why Does Your Brain Keep Second-Guessing This Choice?

Your uncertainty isn’t a personal failing. The human brain craves efficiency through cognitive fluency—the ease with which we process information. When you see “already,” “altogether,” or “almost,” your visual processing system recognizes these as single lexical units. Your brain wants “alright” to work the same way because it follows an established pattern.

The confusion stems from a linguistic civil war. English underwent lexical consolidation for centuries, merging two-word phrases into single words. This process gave us dozens of accepted compounds. Yet “alright” got stuck in limbo, trapped between descriptive reality (millions use it daily) and prescriptive authority (style guides still reject it).

Truth is, you’re caught between two competing forces: natural language evolution and institutional gatekeeping. That tension lives in your head every time you type this word.

Core Concepts and Historical Evolution

The story of “alright” mirrors broader shifts in how English absorbs change. Since the 1880s, writers have used this single-word form, yet dictionaries and editors continue marking it incorrect. The historical record reveals why this particular word became a battleground.

Etymology and the Path of Lexical Consolidation

“All right” emerged in the early 1600s as a two-word phrase. “All” functioned as an intensifier meaning “completely” or “entirely.” “Right” carried its standard meaning of “correct” or “proper.” Together, they created emphasis: not just right, but completely right.

English has a documented pattern of merging “all + [word]” combinations. Consider these accepted consolidations:

- “All ready” → “already” (by 1300s)

- “All together” → “altogether” (by 1300s)

- “All most” → “almost” (by 1200s)

- “All ways” → “always” (by 1300s)

The pattern operates through frequent use. When speakers repeat a two-word phrase thousands of times, the boundary between words weakens. Eventually, writers start representing the phrase as it sounds: unified.

“Alright” followed this exact trajectory. By 1893, it appeared in print regularly. Writers recognized the phonetic reality—when spoken, the phrase sounds like a single word. Yet this particular consolidation faced organized resistance.

Grammatical Mechanics and the Adverbial Modifier Function

Both forms function identically as adverbial modifiers. They modify verbs, adjectives, or entire clauses to indicate adequacy, agreement, or satisfactory conditions.

In the sentence “The test went all right,” the phrase modifies the verb “went,” indicating the test proceeded satisfactorily. Swap in “alright” and the grammatical function remains unchanged. The modification relationship stays intact.

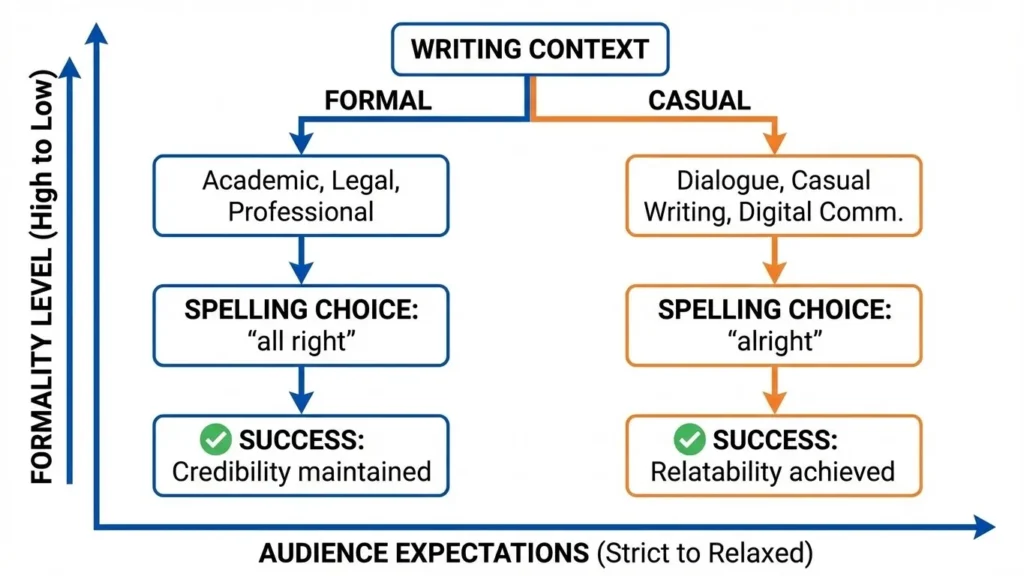

Golden Rule: In formal academic, legal, or professional writing, use “all right.” In casual contexts where tone matters more than tradition, “alright” functions perfectly.

The mechanical truth is simple: spelling variation doesn’t alter grammatical role. Both versions serve as adverbial modifiers with identical semantic weight. The difference lives entirely in the social dimension of language—who accepts which form under what circumstances.

Contextual Examples of Alright vs All Right

Every context creates different expectations. Formal writing demands adherence to established conventions, while casual communication prioritizes speed and naturalness. Understanding when each form thrives requires examining specific scenarios.

Formal and Academic Contexts of Alright vs All Right

In formal writing, “all right” remains mandatory because institutional authorities require it.

Academic sentence: “The methodology appears all right, though the sample size limits generalizability.”

Here, “all right” modifies “appears,” indicating the methodology meets minimum standards. The two-word form signals respect for traditional conventions that academic journals enforce.

Legal contract language: “The terms prove all right for both parties pending final review.”

Legal writing demands the conservative form. Attorneys use “all right” because precedent and clarity matter more than stylistic evolution. Contracts avoid contested spellings.

Casual and Conversational Usage

Casual communication embraces “alright” because brevity matches the informal register.

Text message: “Yeah I’m alright, just tired from the gym”

The single-word form fits the clipped rhythm of digital conversation. Nobody texts “I am all right”—the two-word version sounds stilted and unnatural in this context.

Dialogue in fiction: “You alright?” she asked, concern evident in her voice.

Contemporary dialogue uses “alright” to capture authentic speech patterns. Characters speak in contracted, efficient forms that mirror real conversation.

The Nuance Trap

Native speakers recognize that technically correct choices can sound awkward.

Consider this exchange:

- Correct but wooden: “Are you all right after that fall?”

- Native-sounding: “You alright after that fall?”

Both versions work grammatically, but the second matches actual speech rhythm. This tension between correctness and naturalness creates the persistent confusion writers face.

The trap emerges when you prioritize rules over communication. If your goal is connecting with readers through natural language, the two-word form sometimes backfires. If your goal is satisfying a conservative editor, the single-word form guarantees rejection.

Literary Usage of Alright vs All Right

Writers have wrestled with this spelling choice for over a century. Examining how published authors handled it reveals the slow acceptance trajectory.

Classic Literature Usage

Jane Austen’s letters (1796-1817) consistently used “all right” as two words. The single-word consolidation hadn’t yet emerged in written English. Her characters express agreement through phrases like “That will do all right for our purposes.”

Mark Twain’s correspondence (1870s-1900s) showed occasional “alright” usage, reflecting his commitment to capturing authentic American speech. He represented vernacular speech patterns, even when they violated formal conventions.

Charles Dickens maintained “all right” in his published novels but occasionally used “alright” in personal letters, suggesting he recognized the spoken form as distinct from the written standard.

Modern Stylistic Simulation

Contemporary thriller writers use “alright” to create urgent, realistic dialogue. When characters face danger, they speak in clipped sentences: “Alright, let’s move.” The single-word form accelerates the pace, matching adrenaline-fueled speech.

Literary fiction authors working in stream-of-consciousness styles choose “alright” for internal monologue. The form mirrors how thoughts actually move—compressed and rapid. A character thinking “I’m alright, just need to breathe” sounds more authentic than the formal alternative.

Young adult fiction defaults to “alright” because teenage characters speak in efficient, current patterns. Using “all right” would create tonal dissonance, making dialogue sound like an English teacher wrote it rather than capturing authentic teen voice.

Synonyms and Variations of Alright vs All Right

Understanding related terms clarifies when “alright” or “all right” truly fits the meaning you intend.

Semantic Neighbors and Illocutionary Force

“Acceptable” carries more formality and suggests measured approval: “The proposal is acceptable” implies evaluation rather than casual agreement.

“Adequate” emphasizes sufficiency without enthusiasm: “The performance was adequate” delivers lukewarm assessment.

“Satisfactory” belongs to bureaucratic or evaluative contexts: “Your work is satisfactory” sounds like a performance review, not a conversation.

“Okay” functions as the closest synonym, matching the casual register where “alright” thrives. Both signal agreement, permission, or adequacy without formality.

The illocutionary force—the intended social action of your words—differs across these choices. “All right” can sound clinical or distant. “Alright” feels warmer and more conversational. “Okay” sits somewhere between.

Visualizing the Difference in Alright vs All Right

Regional Variations

British English shows slightly more acceptance of “alright” in published writing. British style guides have softened their absolute prohibitions, acknowledging widespread usage.

American English maintains stricter formal resistance, though casual American writing uses “alright” extensively. The Associated Press Stylebook and Chicago Manual of Style both still prescribe “all right” exclusively.

Australian and Canadian English follow similar patterns to British usage, showing growing acceptance in informal registers while maintaining formal standards.

Common Mistakes and Psychological Triggers

Writers make predictable errors when handling this word pair, driven by specific cognitive patterns.

| Incorrect | Correct | The Fix |

| “I’m doing alright” (formal report) | “I’m doing all right” | Match formality to context |

| “Is that alright with you?” (legal document) | “Is that all right with you?” | Legal writing requires conservative form |

| “The results seem all right” (text message) | “The results seem alright” | Casual contexts prefer brevity |

| “Are you all right?” (dialogue tag) | “Are you alright?” | Natural speech compresses |

The psychological trigger behind most errors: hypercorrection. Writers who learned “alright” is wrong overcorrect by using “all right” in casual contexts where it sounds unnatural. Conversely, writers comfortable with “alright” sometimes forget formal contexts demand the traditional form.

Another trigger: spelling interference from analogy. Your brain sees “already” and “altogether,” then assumes “alright” must work identically. The analogy is logical, but language authorities haven’t accepted it yet.

Stress and time pressure amplify errors. When rushing, you default to whichever form feels automatic, regardless of context appropriateness.

Field Notes from the Editorial Trenches

I spent three hours in 2019 arguing with a junior copywriter who kept changing “alright” to “all right” in character dialogue for a young adult novel. The client brief explicitly requested authentic teen voice, but the writer had internalized the “always wrong” rule so deeply she couldn’t hear how wooden her corrections sounded.

I opened the manuscript file, highlighted every instance, and read them aloud. “You all right?” I said in my flattest monotone. Then: “You alright?” with natural concern. The difference hit her immediately. We discussed how rules serve communication, not the reverse.

That deadline pressure—the manuscript was due to the publisher in 48 hours—forced us to make rapid decisions about where the traditional form genuinely improved the text versus where it sabotaged the author’s voice. I marked “Keep ‘all right’ in narration, restore ‘alright’ in dialogue” and explained the distinction to the author.

The stress of navigating conflicting rules under time constraints taught me something crucial: you need a clear decision framework, not just memorized prohibitions. Know your audience’s expectations, match your tone to context, and choose the form that serves your purpose.

Memory Aid

FORMAL writes it ALL out.

When the context is FORMAL, spell it ALL out as two words: “all right.” When the context lets you relax, one word works “alright.”

Conclusion

You now possess a decision framework that transforms confusion into clarity. “All right” dominates formal writing because institutions move slowly, but “alright” thrives in casual contexts because language evolves through use. In professional correspondence, academic papers, and legal documents, “all right” prevents criticism. In dialogue, text messages, and casual blogging, “alright” sounds natural.

FAQs

No. Major style guides including AP, Chicago, and MLA still prescribe “all right” for formal contexts.

Authors use “alright” in dialogue and informal narration to capture authentic speech patterns. Publishers accept it in fiction because realistic character voice matters more than strict adherence to style guide rules.

Avoid it. Resumes demand conservative, traditional language that doesn’t give hiring managers any reason to question your professionalism. Use “all right” in any situation where someone might judge your language choices, including job applications, cover letters, and professional correspondence.

Yes. Official Scrabble dictionaries include “alright” as an acceptable word because dictionaries describe actual usage, even when style guides prescribe against it.

Context determines perception. In a text message or casual blog post, “alright” signals natural, contemporary writing. In a graduate school essay or business proposal, it signals ignorance of formal conventions.

“Already” consolidated centuries earlier, before prescriptive grammar authorities established rigid rules in the 1800s. By the time grammarians started codifying “correct” English, “already” had achieved such widespread use that fighting it seemed futile. “Alright” emerged during the height of prescriptive grammar’s power, giving authorities a chance to resist its adoption.

Slightly. British style guides show more flexibility than American ones, though both still prefer “all right” in formal writing.

No. Both forms carry identical meaning and function identically in sentences. The only difference involves social perception—who accepts which spelling under what circumstances.